With the rising costs of health insurance, many people are looking for ways to reduce their costs. Since not all insurance packages include vision insurance, many people wonder, do I need vision insurance?

Standard Vision Insurance

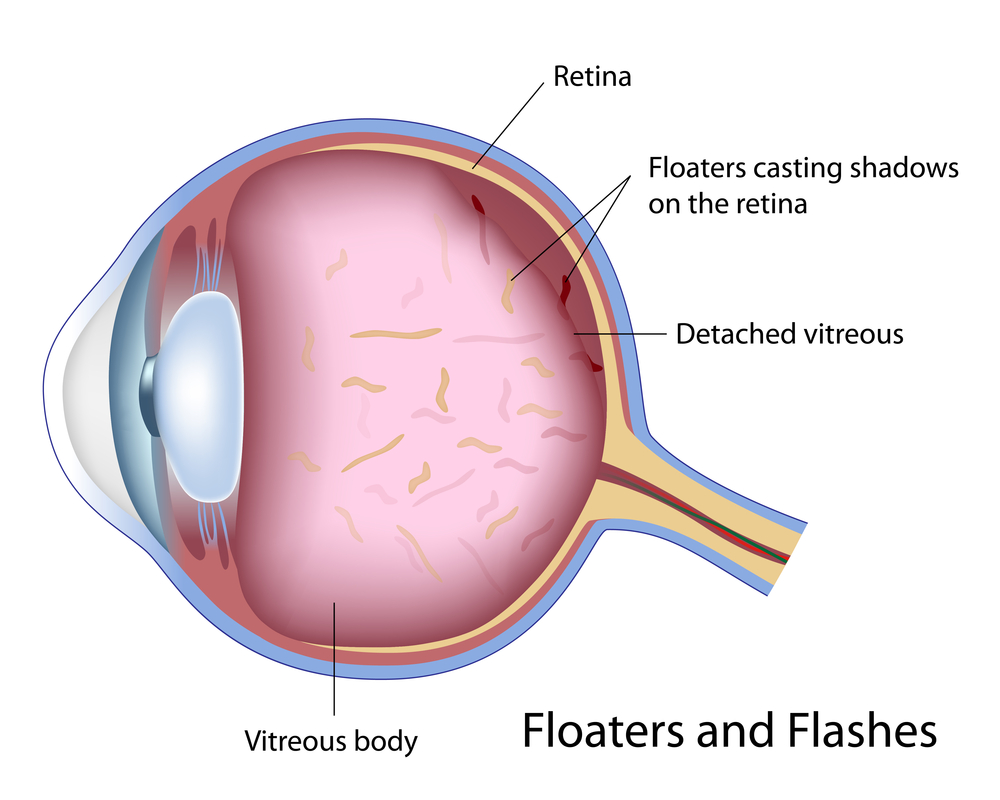

Vision insurance is a type of health insurance that entitles you to specific eye care benefits such as routine eye exams and other procedures, as well as a specified dollar mount or discount for the purchase of eyeglasses and contact lenses. It only supplements regular health insurance and is designed to help reduce your costs for routine preventative eye care and eyewear.

You can get vision insurance as part of a group, such as your employer, an association, etc., through a government program such as Medicare or Medicaid, or as an individual. It is often a benefit linked to your regular HMO (health maintenance organization) or PPO (preferred provider organization) health insurance.

There are two primary vision insurance plans available:

- Vision Benefits Package – provides free eye care services and eyewear within a fixed dollar amount for which you pay an annual premium or membership fee and a small co-pay. It may also include a deductible.

- Discount Vision Plan – provides eye care and eyewear at a discounted rate after you pay an annual premium or membership fee.

Both insurance plans generally include:

- Annual eye exams

- Eyeglass frames (usually once every 24 months)

- Eyeglass lenses (usually once every 24 months)

- Contact lenses (usually once every 24 months)

- Discounted rates for LASIK and PRK

Here is where you can check for a list of some vision insurance providers.

Medicare and Medicaid

Different kinds of vision care are included in the US government programs, Medicare and Medicaid. These programs are for qualifying American age 65 and older, individuals with specific disabilities and people with low income.

The Types of Medicare For Vision:

- Medicare Part A (Hospital Insurance) –Medical eye problems that require a hospital emergency room attention, but routine eye exams are NOT covered.

- Medicare Part B (Medical Insurance) – Visits to an eye doctor that are related to an eye disease, but routine eye exams are NOT covered.

- Medicare Part D (Prescription Drug Coverage) – Will help pay for prescription medications for eye diseases.

If you have Medicare Parts A & B you are generally eligible for the following vision coverage, however, there is a deductible before Medicare will start to pay, at which point you will still be paying a percentage of the remaining costs.

- Cataract surgery – covers many of the cost including a standard intraocular lens (IOL). If you chose a premium IOL to correct your eyesight and reduce your need for glasses, you must pay for this added cost out-of-pocket.

- Eyewear after cataract surgery – one pair of standard eyeglasses OR contact lenses.

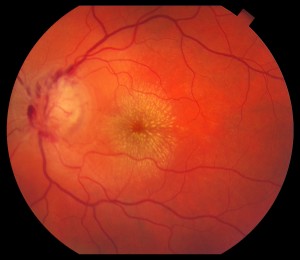

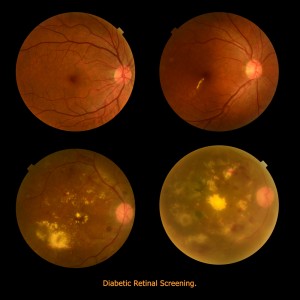

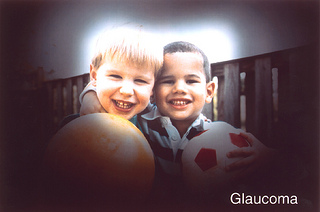

- Glaucoma screening – an annual screening for people at high risk for glaucoma, including people with diabetes or a family history, and African-Americans whom are 50 or older.

- Ocular prostheses – costs related to the replacement and maintenance of an artificial eye.

There is also Medicare Supplement Insurance (Medigap) which is sold by private insurance companies to supplement only Medicare Parts A & B. It is intended to cover your share of the costs of Medicare-covered services including coinsurance, co-payments and deductibles. For more details about Medicare plans and coverage check their website or call 800-633-4227.

Medicaid is the US health program that gives medical benefits to low-income people who may have no or inadequate medical insurance. A person eligible for Medicaid may be asked to make a co-payment at the time medical service is provided. Vision benefits for children under the age of 21 include eye exams, eyeglass frames and lenses. Each state determines how often these services are provided and some states offer similar vision services to adults. To learn more about Medicaid eligibility requirements and vision benefits call your state’s Medicaid agency or visit their website.

Defined Contribution Health Plans

A way to lower your vison care costs is to take part in a defined contribution health plan (DCHP). You are given a menu of health care benefits to choose from where a portion of the fees you receive for health coverage come from money that is deducted from our paycheck before federal, state and social security taxes are calculated. Four types of DCHP are:

Cafeteria Plans – your employer takes a portion of your salary and deposits it into a non-taxable account for health care spending. The amount taken depends on the number and costs of the benefits you select.

Flexible Spending Accounts (FSA) – your employer takes a predetermined portion of your pre-tax salary and deposits it into health care account for you to pay medical expenses. But generally preventative care such as routine eye exams and are not reimbursable. Nor are eyeglasses and contact lenses reimbursable. You would need to verify with your employer. If you do not use all the money at the end of a 12 month period, the money goes back to your employer.

Health Reimbursement Arrangement (HRA) – this is similar to an FSA except you can use it for preventative care like eye exams and you do not lose the money if it isn’t spent within a certain time period as it can be carried from year to year.

Health Savings Account (HSA) – it can be employer-sponsored of you can set up one independently; however you must purchase a high-deductible health insurance plan to open an HSA and you cannot exceed the annual deductible of your health insurance plan. You cannot be enrolled in Medicare of be a depended on someone else’s tax return. You can use it for preventive care such as eye exams. You can learn more about HSAs by visiting the US Treasury’s website.

There are a variety of options when it comes to vision insurance. You just need to determine your needs and ask providers the correct questions.

4/14/15

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Vice President of Development

Discovery Eye Foundation