5/29/14

Employment Challenges Faced by Older Persons with Visual Impairments

Growth in Number of Older Persons with Vision Loss

May is designated as “Older Americans Month” and last year’s theme “Unleash the Power of Age” seemed an appropriate title for this article with the number of baby boomers who are coming down the pike. In fact, according to the U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the annual growth rate of “boomers” (those 55 and older) is projected to be 4.1 percent, 4 times the rate of growth of the overall labor force. Indeed, the Governmental Accountability Office estimates that by 2015 (just next year!!), older workers will comprise one-fifth of the nation’s workforce.

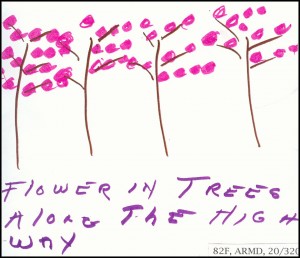

At the same time, the number of older persons with vision loss are growing dramatically due to age-related eye conditions such as macular degeneration . The 2011 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Preliminary Report indicated that an estimated 21.2 million adult Americans (or more than 10% of all adult Americans) reported they either “have trouble” seeing, even when wearing glasses or contact lenses, or that they are blind or unable to see at all. The survey also indicated that 12.2% of Americans 65 to 74 years of age and 15.2% of Americans 75 years of age report having loss of vision. These estimates only include the non-institutionalized civilian population.

Economic Burden of Vision Loss and Aging

According to Prevent Blindness, disorders of the eye and resulting vision loss result in a major economic burden to society, for all ages, but most dramatically with people 65 years of age and older: 77.27 billion of direct and indirect costs . Loss of productivity is estimated to be almost $25 billion for the 65 plus population.

Older People Want to Continue to Work

The loss of productivity costs are of particular concern given the fact that older people, including those with vision loss, want to continue to work. In fact, older persons are staying in the labor market beyond the usual retirement age. This is due to many reasons: people are living longer and often are in good health; because of the downturn in the economy, some need to work beyond the usual retirement age to meet to supplement diminished retirement funds; and some are looking for social engagement through the workplace.

Assets Versus Perceptions

Experienced workers who are older offer many assets to employers such as: an understanding of the expectations of employers; respect for co-workers and supervisors; loyalty; and skills and knowledge based on prior work experience. However, a major dichotomy is occurring in our society regarding older workers: “…companies are struggling with the large numbers of older workers who are retiring, and that the brain drain is a matter of concern to many…While the loss of experienced staff is a challenge that all companies must address, technology has improved the workplace and the work environment by enabling workers of all ages to complete work from other locations…Evidence shows that ageism, stereotypes, and misinformation about mature persons continue to be issues across all segments of society, including the workplace. … studies revealed that the positive perceptions characteristic of older workers held by managers include their experience, knowledge, work habits, attitudes, commitment to quality, loyalty, punctuality, even-temperedness, and respect for authority. These same studies also reveal some negative perceptions held by managers about the mature worker: inflexibility, unwillingness or inability to adapt to new technology, lack of aggression, resistance to change, complacency….. While the results of these findings may appear confusing or contradictory, they clearly focus on the precise and delicate balance between positive and negative perceptions that, depending on the industry or work environment, may affect a manager’s decision to hire, retain or advance an older worker.”

Kathy Martinez, Assistant Secretary of the Office of Disability Employment Policy at the Department of Labor, feels that this dichotomy, as it relates to people with disabilities, will not really change until disability becomes more of an environmental issue than a personal issue and that workplace flexibility is critical in terms of time, place, and task. (“Public Policy and Disability: A Conversation about Impact”, Disability Management Employment Coalition conference, April 1, 2014).

Challenges of Obtaining and Retaining a Job for Older Persons with Vision Loss

In addition to the negative perceptions noted above, older persons who experience vision loss, have additional challenges: learning to live with vision loss, dealing with the workplace to retain or obtain a job, working with a disability including having to learn new skills such as speech access for a computer, getting transportation to and from work (if they keep or land a job), dealing with co-workers and even managers who often don’t know what to say or do. Those persons with low vision or no vision whose medical condition is stabilized and with appropriate reasonable accommodations as assured by the Americans with Disability Act (ADA), can continue to be productive members of the workforce thereby contributing to the profitability of the business and to their quality of life.

An informal review of the latest available data submitted by public vocational rehabilitation agencies indicates the following: In 2011, there were 9609 blind and visually impaired individuals who obtained jobs through the vocational rehabilitation agencies; of these 505 (or 5%), were 65 years of age and older. We truly need to “unleash” the power of age in this country!

Resources

These resources listed can help older individuals with vision loss, employers, and professionals working with individuals with vision loss. The American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) hosts a family of web sites with information that can help older persons with adjusting to and living with vision loss, information on how to find and apply for jobs, adaptations to the work environment and assistive technology and workplace accommodations, and mentors who are blind or visually impaired and are willing to assist others with career choices. These sites can help individuals interested in working or retaining employment as well as employers seeking to know what to do. AFB has a directory of services for each state, which includes state vocational rehabilitation agencies charged with helping people with vision loss with the adjustment and career needs.

AFB Links

Information related to living with vision loss:

Visionaware.org/gettingstarted

Information about working:

Visionaware.org/work

AFB.org/careerconnect

Data base on how to find public and private agencies:

AFB.org/directory

Online courses including “Employment of Older Persons”, technology, etc. (for professionals):

Elearn.afb.org

Other Resources

Department of Labor funded Job Accommodations Network

http://askjan.org/

JAN provides consultation to employers and job seekers about the wide range of accommodations which can help to select the appropriate technology and job restructuring accommodations.

Department of Labor Office of Disability Policy

http://www.dol.gov/odep/topics/OlderWorkers.htm

Section on research and reports on employment of older workers.

Gil Johnson

Gil Johnson

Contributing author to VisionAware ™

American Foundation for the Blind

![Mogk_Lylas_11C[1]](https://discoveryeye.org/wp-content/uploads/Mogk_Lylas_11C1.jpg)