Costume Contact Lenses such as cat eyes or zombie may make your Halloween costume a bit more frightful although wearing those lenses without a prescription can be more terrifying, as it could result in vision loss or even blindness.

Costume Contact Lenses such as cat eyes or zombie may make your Halloween costume a bit more frightful although wearing those lenses without a prescription can be more terrifying, as it could result in vision loss or even blindness.

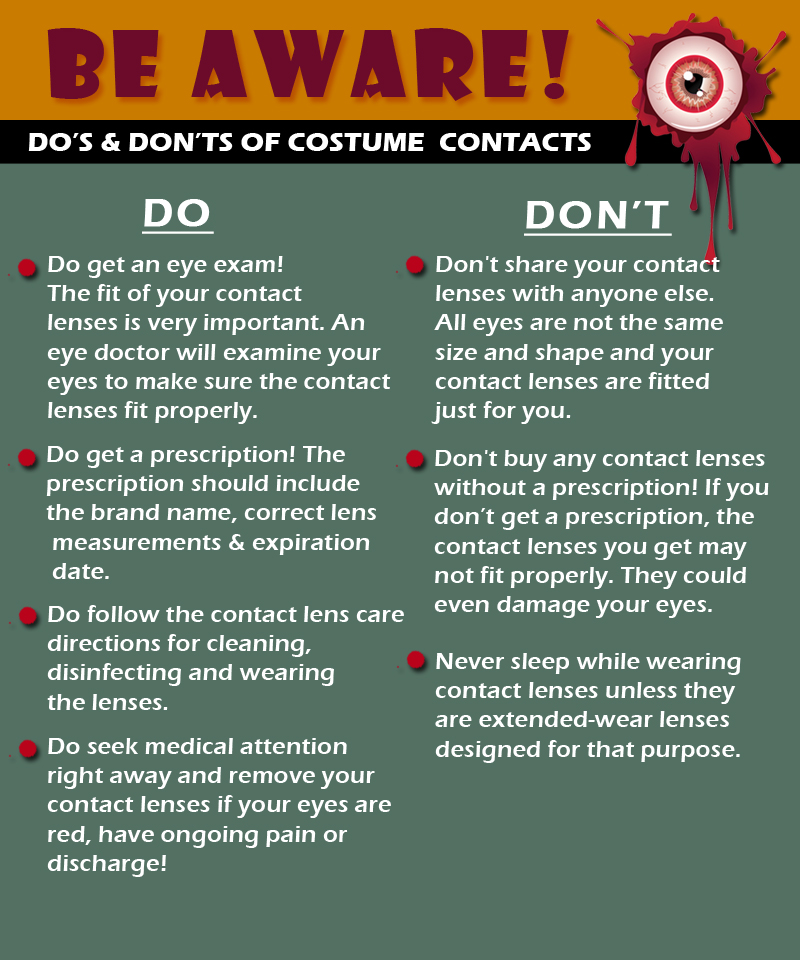

You can buy contact lenses, including decorative contact lenses, from your eye doctor or on the Internet. It’s very important that you only buy contact lenses from a company that sells FDA-cleared or approved contact lenses and requires you to provide a prescription. Even if you don’t wear corrective lenses you still need to get fitted properly.

Remember — Buying contact lenses without a prescription is dangerous!

Right now there are a lot of products that you can buy without a prescription but they may not be safe or legal.

You should NEVER buy lenses from:

- street vendors

- salons or beauty supply stores

- boutiques

- flea markets

- novelty stores

- Halloween stores

- convenience stores

- beach shops

- internet sites that do not require a prescription

Know the Risks –

Wearing costume contact lenses can be risky, just like the contact lenses that correct your vision. Wearing any kind of contact lenses, including costume lenses, can cause serious damage to your eyes if the lenses are obtained without a prescription or not used correctly.

These risks include:

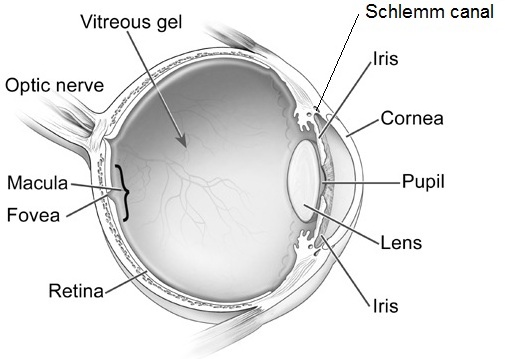

- A cut or scratch on the top layer of your eyeball (Corneal Abrasion)

- Allergic reactions like itchy, watery red eyes

- Decreased vision

- Infection

- Blindness

Signs of possible eye infection:

- Redness

- Pain in the eye(s) that doesn’t go away after a short period of time

- Decreased vision

If you have any of these signs, you need to see a licensed eye doctor (optometrist or ophthalmologist) right away! An eye infection could become serious and cause you to become blind if it is not treated.

This Halloween season DEF wants to remind you of the importance of eye safety and to make sure to take the proper steps in ensuring the proper contact lenses.

Tom Sullivan

Tom Sullivan

Summer time is officially here and everyone enjoys a dip in a nice, cool pool during the summer months. While swimming is a great form of exercise and a relaxing way to cool down, the water can be hard on your eyes.

Summer time is officially here and everyone enjoys a dip in a nice, cool pool during the summer months. While swimming is a great form of exercise and a relaxing way to cool down, the water can be hard on your eyes. Wear Goggles – Wear a pair of swim goggles every time you swim. Goggles keep pool chemicals out of your eyes.

Wear Goggles – Wear a pair of swim goggles every time you swim. Goggles keep pool chemicals out of your eyes. Wash Your Eyes – Immediately after swimming, splash your closed eyes with fresh tap water. This washes chlorine and other chemicals off your eyelids and eyelashes.

Wash Your Eyes – Immediately after swimming, splash your closed eyes with fresh tap water. This washes chlorine and other chemicals off your eyelids and eyelashes. Use Eye Drops – Use over-the-counter lubricating eye drops before and after swimming to keep the tear film balanced and eyes comfortable.

Use Eye Drops – Use over-the-counter lubricating eye drops before and after swimming to keep the tear film balanced and eyes comfortable. Stay Hydrated – Don’t forget to drink plenty of water. Staying well hydrated is an important part of keeping your eyes moist and comfortable.

Stay Hydrated – Don’t forget to drink plenty of water. Staying well hydrated is an important part of keeping your eyes moist and comfortable.

Summer is almost over and it’s back to school season. As parents, many of us are busy ensuring our kids are ready and prepared for the new year; worrying about school supplies, new clothes, and new haircuts. There is always a long list of things to do before school starts. But something that often gets overlooked is getting your child’s eyes examined annually.

Summer is almost over and it’s back to school season. As parents, many of us are busy ensuring our kids are ready and prepared for the new year; worrying about school supplies, new clothes, and new haircuts. There is always a long list of things to do before school starts. But something that often gets overlooked is getting your child’s eyes examined annually. Vision loss is feared more than the loss of any other sense and is considered to affect the quality of life more than most other issues. When it comes to children, even partial vision loss can be damaging because it can affect the way that your child learns and develops. There are several different types of issues that may affect your child’s vision. Awareness is key to prevention and treatment.

Vision loss is feared more than the loss of any other sense and is considered to affect the quality of life more than most other issues. When it comes to children, even partial vision loss can be damaging because it can affect the way that your child learns and develops. There are several different types of issues that may affect your child’s vision. Awareness is key to prevention and treatment. Amanda Duffy

Amanda Duffy