1/8/15

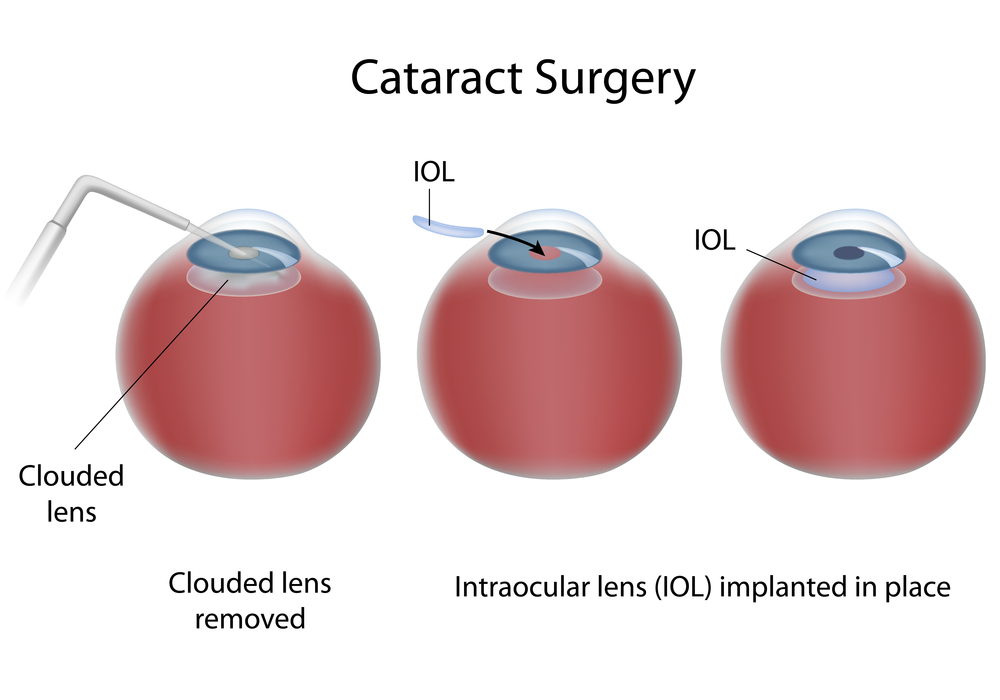

The eye works like a camera, specifically a digital camera. There is the front lens of the camera (cornea), the aperture (iris), the film (retina), and a cable to take the image to the brain (optic nerve). This “camera” also has an additional lens – the natural crystalline lens, which lies behind iris. This natural lens is flexible when we are young, allowing us to focus at distance then instantaneously up close. Around age 40-45, this natural lens starts to stiffen, necessitating the need for reading glasses for most people. This stiffening is the beginning of the aging process that eventually leads to formation of a cataract. We refer to the lens as a cataract when it becomes sufficiently cloudy to affect ones quality of vision. In general, cataract surgery is one of the safest and most successful of all surgeries performed. The basics of cataract surgery in eyes with keratoconus is very similar to non-keratoconic eyes.

In general, cataract surgery is one of the safest and most successful of all surgeries performed. The basics of cataract surgery in eyes with keratoconus is very similar to non-keratoconic eyes.

Keratoconus (KC) affects this “camera” by causing the front lens (cornea) to bulge. This causes the optics to be distorted. In many cases, this can be corrected for with hard contact lenses (CL) or spectacles; in other cases a corneal transplant may be necessary. When it comes time for cataract surgery in the setting of KC, there are several factors that need to be considered.

Corneal Stability

The first thing to be considered is the stability of your cornea. In general, KC progresses more in your late teens to early twenties, and then stabilizes with age. A very exciting treatment for KC is collagen crosslinking. This treatment is meant to stiffen the cornea to prevent instability that is inherent to KC. This treatment promises to stop the progression of KC at a young age. Fortunately, with age, the cornea naturally crosslinks and stiffens, therefore when it comes time for cataract surgery, there is little chance of the progression of KC. Your doctor needs to choose the appropriate intraocular lens (IOL) to refocus your eye after surgery. Two of the most important factors in IOL selection are the length of your eye and the shape of your cornea. Long term CL wear can mold your cornea. It is important to assure that you stay out of your CLs long enough for your cornea to reach its natural shape. Depending on how long you have worn your CLs, it may take several months for the cornea to stabilize. This time can be challenging as your vision will be suboptimal (because you can’t wear CLs), and will be changing (as your cornea reaches its natural shape). When your cornea does stabilize, it is important to determine whether the topography (shape) is regular or irregular. This “regularity” is also known as astigmatism. If the astigmatism is regular, light is focused as a line – generally, this distortion can be fixed with glasses. However, if the astigmatism is irregular, light cannot be focused with glasses, and hard CLs are needed to provide optimal focusing. If you have had a corneal transplant, I generally recommend all your sutures to be removed to allow your new cornea to reach its natural shape.

IOL Selection

The second thing to be considered is the type of IOL. IOLs allow your doctor to refocus the optics of your eye after surgery. In many cases, the correct choice of IOL may decrease your dependence on glasses or CLs. There are several factors that are important when considering the correct IOL for a keratoconic patient. The amount and regularity of your astigmatism plays a very significant role in IOL selection. In general, there are four types of IOLs available in the US – monofocal, toric, pseudo-accomodating, and multifocal. In general I do not recommend multifocal IOLs in patients with KC. These IOLs allow for spectacle independence by spitting the light energy for distance and near, however, with an aberrated cornea (which is what happens in KC), these IOLs do not fare well. If there is a low amount of regular astigmatism or irregular astigmatism, your best bet is a monofocal IOL. This is the “standard” IOL that is covered by your health insurance. If you have higher amounts of astigmatism that your doctor determines is mostly regular, you may benefit from a toric (astigmatism-correcting) IOL. These IOLs can significant improve your uncorrected vision and really decrease your dependence on glasses. It is important to realize that monofocal and toric IOLs only correct vision at one distance. With a monofocal IOL you still can wear a CL to fine-tune your vision, however, with a toric IOL, in general you will need glasses for any residual error. There is a pseudo-accomodating toric IOL available, and this may be a good option if you are trying to decrease your dependence on glasses and correct some of your astigmatism. These IOLs are relatively new to the US market.

If You Had A Corneal Transplant

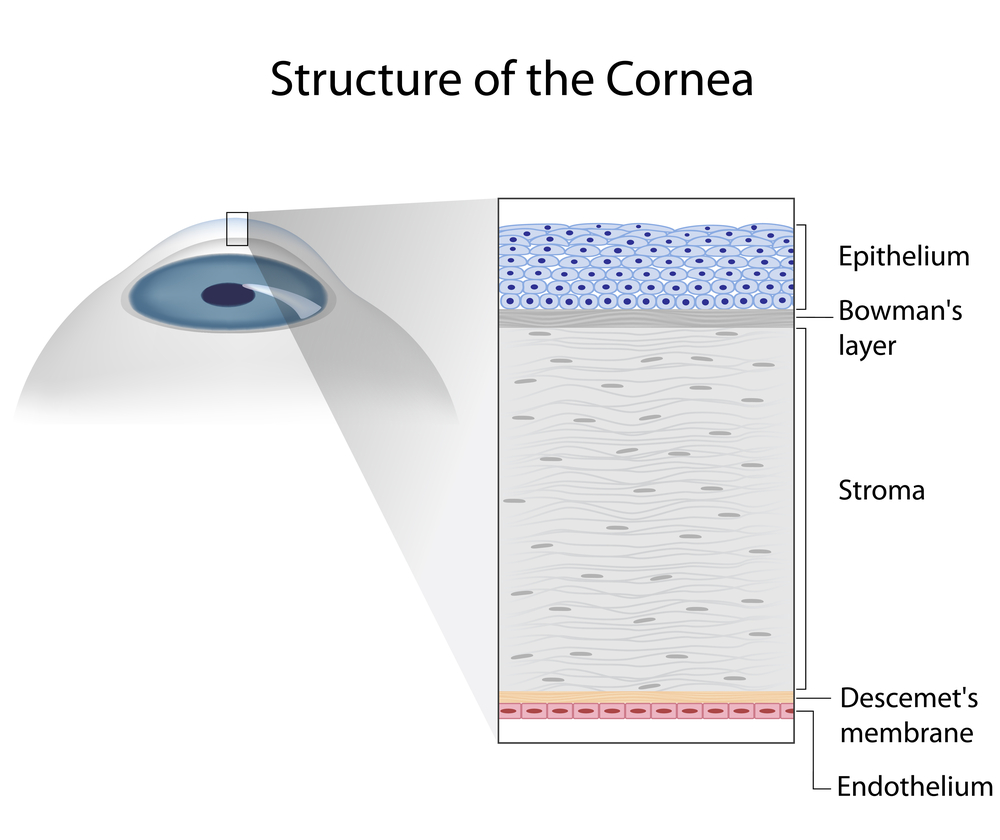

In the setting of a corneal transplant many of the same factors need to be considered – stability of the graft, choice of IOL, etc. In addition, the health of the graft has to be judged. Prior to cataract surgery in my patients with corneal transplants, I make sure to remove all of their sutures and give the cornea time to stabilize (just as if they were a CTL wearer). If you are a CL wearer, the same rule of being out of the TL until the topography is stable applies. The health of a transplant needs to be established prior to undergoing cataract surgery. The cornea has five main layers to it – the back layer (inside) is called the endothelium. This layer is responsible for “pumping” fluid out of the cornea, allowing it to stay clear. In all eyes there is a loss of endothelium cells with cataract surgery. I generally perform a “specular microscopy,” which allows me to visualize and quantify the corneal endothelium prior to surgery. This allows me to risk stratify you before your surgery. It is important to realize that corneal transplants have a lifespan and may have to be repeated in the future.

the back layer (inside) is called the endothelium. This layer is responsible for “pumping” fluid out of the cornea, allowing it to stay clear. In all eyes there is a loss of endothelium cells with cataract surgery. I generally perform a “specular microscopy,” which allows me to visualize and quantify the corneal endothelium prior to surgery. This allows me to risk stratify you before your surgery. It is important to realize that corneal transplants have a lifespan and may have to be repeated in the future.

Keep in mind, there is some uncertainty in biometry (the process of selecting an IOL) in all eyes – this error can be higher in keratoconic eyes. This highlights why assuring stability is important. Equally important is picking the correct IOL for your situation. Also, keep in mind that I have discussed generalities in this article. Your individual case could be different. This is a conversation best left between you and your surgeon. In general, cataract surgery and keratoconus or a corneal transplant can be a very safe and effective way in restoring vision.

Sumit (Sam) Garg, MD

Sumit (Sam) Garg, MD

Interim Chair of Clinical Ophthalmology and Medical Director

Gavin Herbert Eye Institute at the University of California, Irvine