Two hallmark DEF-funded projects are converging, providing great hope for those facing vision loss from retinitis pigmentosa (RP) or age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

The first project, headed by UC Irvine researchers Drs. Henry Klassen and Jing Yang, concentrates on putting human retinal progenitor cells into the eyes of those with RP in order to rescue damaged retinal cells. That project is currently in Phase II clinical trials, progressing toward FDA approval.

According to DEF Research Director Dr. Cristina Kenney, if the project is approved by the FDA for use with RP, the next question is: What other diseases might these retinal progenitor cells be used for? That’s where a second DEF-funded project comes in.

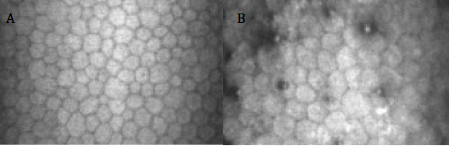

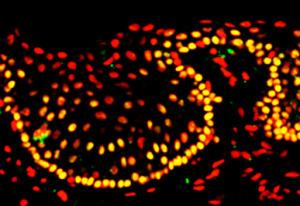

Kenney is working on a “personalized” cybrid cell model to screen agents that specifically target the mitochondria in AMD cells. To date, the researchers have different cybrid cell lines representing 60 different individuals with eye diseases. They are looking for novel mechanisms to protect AMD cells from dying.

Yang and Kenney are now working together to determine whether the retinal progenitor cells can be the agent that rescues AMD cybrids. “When we take the mitochondria from AMD patients and put them into healthy retinal cells, which makes cybrids, we have shown that these AMD cybrid cells will start to die. So we used that model to ask the question: How do we rescue them?” Kenney says.

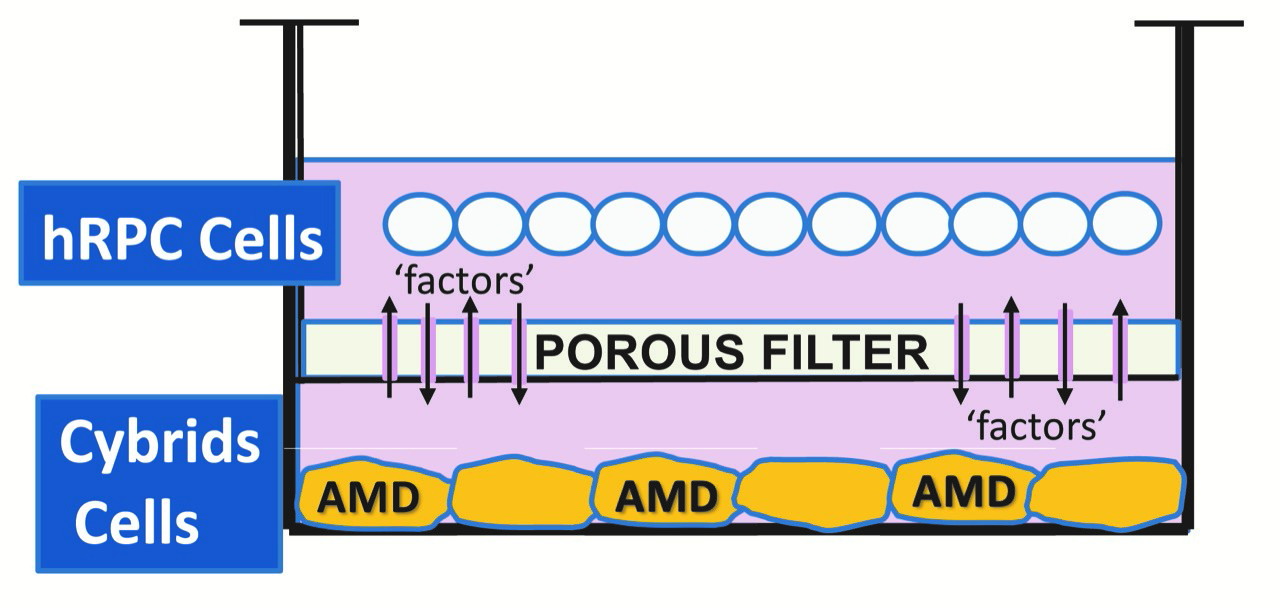

Kenney and Yang developed a tissue culture model, where the retinal progenitor cells are grown in one part of a chamber, and the AMD cybrids are grown in another part of chamber, surrounded by culture medium. There is a porous separator between the two chambers through which the cells can communicate.

“We are finding that the retinal progenitor cells produce a factor that protects the AMD cybrids,” Kenney says. “This provides promising evidence that these proprietary retinal progenitor cells that are being tested for treating RP also may be helpful in AMD patients.”

“DEF has been supporting both these retina-related projects for quite some time, and it’s very exciting to see them coming together to potentially treat both RP and AMD.”