10/30/14

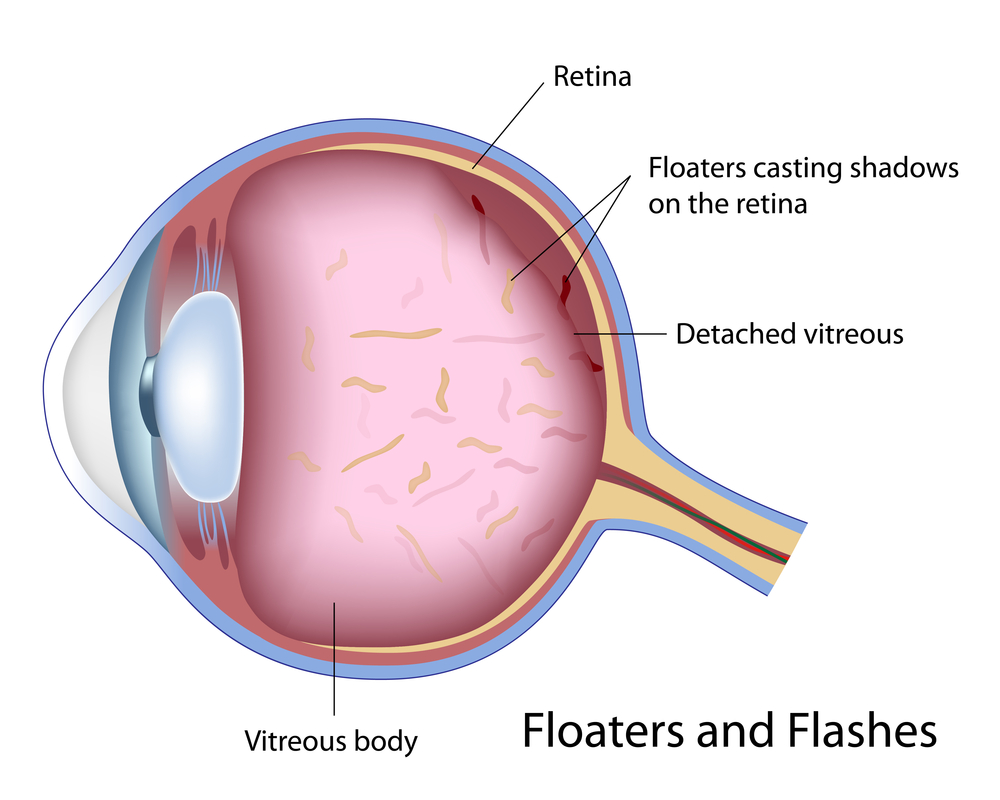

Have you ever noticed floaters in your vision? Perhaps they looked like a bunch of small dots or maybe a cobweb swaying back and forth in your visual field. Were the floaters associated with flashing lights that made you think there was a lightning storm coming your way? These are typical symptoms of a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), and if you have had these symptoms you are far from alone.

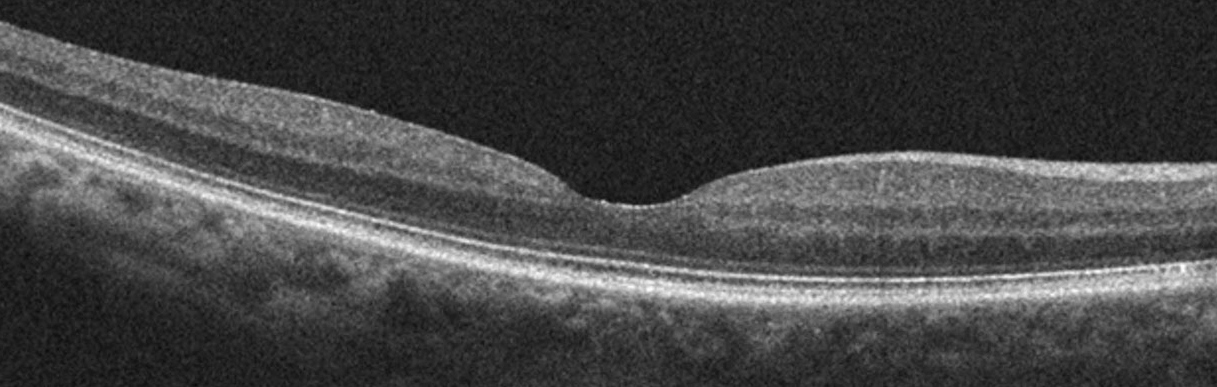

PVD is a natural process that occurs in the majority of people usually over the age of 50. The vitreous is a jelly-like substance that occupies the back portion of the eye. The vitreous is comprised primarily of water, which accounts for 99% of its volume, and the remaining 1% includes proteinaceous substances such as collagen fibers as well as hyaluronic and ascorbic acids. The collagen fibers act as a scaffold to allow the vitreous to maintain a formed shape as well as provide a means for the vitreous to attach to the retina, which is the light-sensitive tissue that lines the inner back wall of the eye and is critical for vision. As we age, changes in these fibers cause the vitreous to lose its shape and eventually pull away from the retina. When the vitreous separates from the retina, this is called a PVD.

As we age, the collagen components of the vitreous can clump together and are free to float in the eye. When the vitreous separates from the retina during the development of a PVD, the floaters may become more noticeable or numerous. It is common for patients to describe floaters of different shapes and sizes, and patients may notice just one or in some cases many. In many people, a PVD develops slowly and there may be no symptoms or just a few annoying floaters. In others, a PVD may occur abruptly and cause more dramatic symptoms that can be very anxiety provoking.

Since the normal process of PVD development involves the vitreous tugging on the retina until it can fully separate, this tugging can result in flashing lights that can commonly appear in the peripheral, or side, vision. These flashing lights are sometimes described as lightning streaks, and patients may notice them more readily in settings with low ambient light. The flashes of light typically resolve once the vitreous has fully separated from the retina and the tugging has ceased.

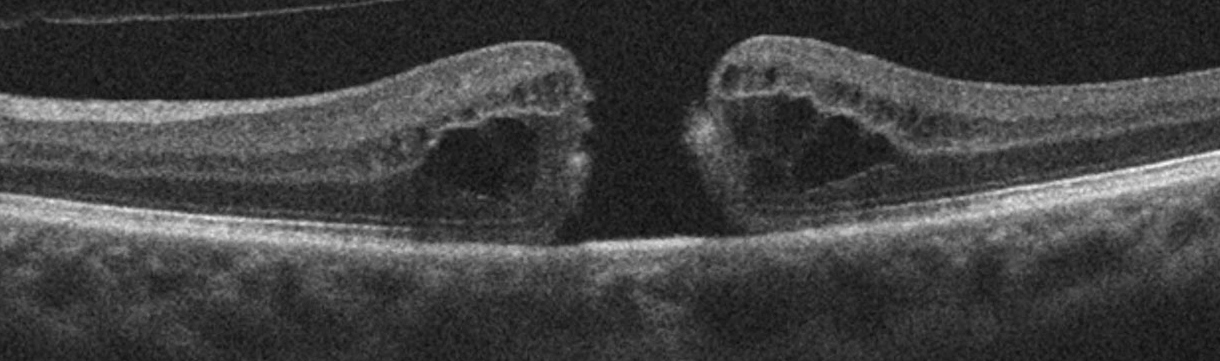

The good news is that PVD is usually harmless in the vast majority of cases, and the annoying floaters will become less bothersome over time. In approximately 5-10% of cases, the vitreous can tug too hard on the retina as it tries to separate and it may pull a hole or tear in the retina. Tears in the retina can predispose to retinal detachment, which is a serious condition that can lead to permanent vision loss.

It is important to recognize that the typical symptoms of a regular PVD are often similar to a PVD with an associated tear. For this reason, it is recommended that all patients with the new onset of floaters or flashes have a dilated eye exam. If a retinal tear or detachment is discovered, early treatment can help prevent loss of vision.

Treatment for PVD usually involves simple observation. With time, the flashes will go away, and the floaters will become less noticeable. More recently, few providers have claimed that floaters can be treated with a laser in order to make them less noticeable. I would caution that this is not mainstream therapy at the current time, and I do not advise my patients to pursue this option. Another treatment possibility is vitrectomy surgery, where the vitreous gel is removed as part of a surgical procedure. Due to safety advances in vitrectomy surgery, this is now a potential option for the rare patient who has floaters that are so numerous and bothersome that they are negatively impacting their activities of daily living. For the vast majority of patients this is not necessary.

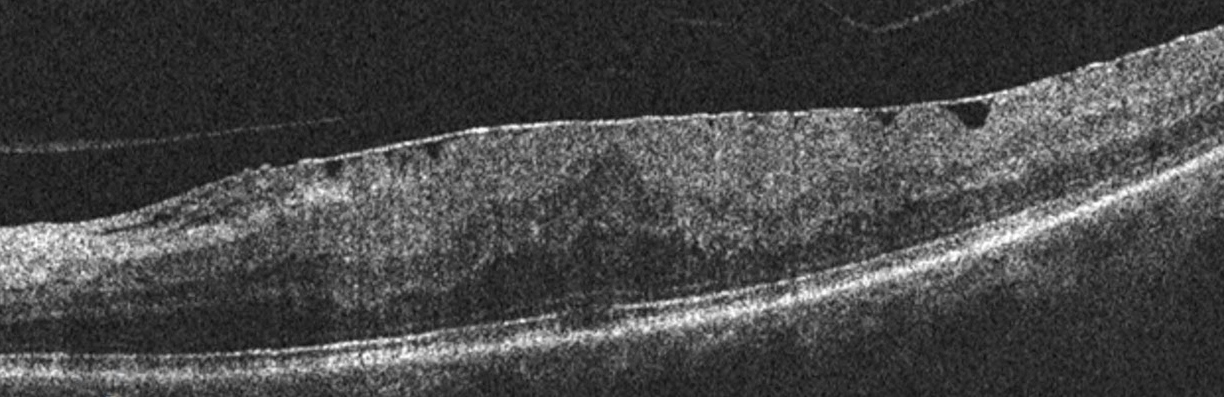

When I see a patient with a PVD, I often recommend one follow-up visit in 4-6 weeks to make sure there are no retinal holes or tears that have developed in the interim. If the other eye has not had a PVD yet, I will counsel them that a PVD will most likely develop in that eye within the next few years, and when it does they need to be examined. I will also discuss the retinal detachment warning signs. Patients with retinal detachment will not only have symptoms similar to PVD, including flashes and floaters, but in addition they may also notice what looks like a black shade or curtain that starts in the peripheral vision and extends towards the central vision. My patients are taught that this symptom requires an immediate examination.

In conclusion, PVD is a natural process that the majority of people will experience in their lives. The symptoms can range from having no symptoms at all to many floaters with associated lightning flashes. In the majority of patients, there is no damage to the eye or threat to the vision. A dilated exam is recommended to look for possible holes or tears in the retina, and if these are uncovered, prompt treatment can prevent vision loss.

Daniel D. Esmaili, MD

Daniel D. Esmaili, MD

Retina Vitreous Associates Medical Group