Basketball, Baseball and Air/Paintball Guns Top the List of Leading Causes of Eye Injuries

More than 40 percent of eye injuries that occur every year are related to sports or recreational activities. A recent study found that about 30,000 people in the U.S. went to an emergency department with a sports-related eye injury, a substantially higher estimate than previously reported. Three sports accounted for almost half of all injuries: basketball, baseball and air/paintball guns.

More than 40 percent of eye injuries that occur every year are related to sports or recreational activities. A recent study found that about 30,000 people in the U.S. went to an emergency department with a sports-related eye injury, a substantially higher estimate than previously reported. Three sports accounted for almost half of all injuries: basketball, baseball and air/paintball guns.

Basketball was the leading cause of injury in males, followed by baseball/softball, and air/paintball guns. Baseball or softball was the leading cause among females, followed by cycling and soccer.

In support of Sports Eye Safety Month in April, we are offering athletes of all ages guidance on how to protect their eyes.

Sports-related injuries can range from corneal abrasions and bruises on the lids to more serious, vision-threatening internal injuries, such as a retinal detachment and internal bleeding. About one-third of sports related eye injuries happen to kids.

The good news is that simply wearing protective eyewear can prevent about 90 percent of eye injuries. Follow these tips to save your vision:

- Wear the right eye protection: For basketball, racquet sports, soccer and field hockey, wear protection with shatterproof polycarbonate lenses.

- Put your helmet on: For baseball, ice hockey and lacrosse, wear a helmet with a polycarbonate face mask or wire shield.

- Know the standards: Choose eye protection that meets American Society of Testing and Materials (ASTM) standards. See the Academy’s protective eyewear webpage for more details.

- Throw out old gear: Eye protection should be replaced when damaged or yellowed with age. Wear and tear may cause them to become weak and lose effectiveness.

- Glasses won’t cut it: Regular prescription glasses may shatter when hit by flying objects. If you wear glasses, try sports goggles on top to protect your eyes and your frames.

Virtually all sports eye injuries could be prevented by wearing proper eye protection. That is why athletes are encouraged to protect their eyes when participating in competitive sports.

Anyone who experiences a sports eye injury should immediately visit an ophthalmologist, a physician specializing in medical and surgical eye care.

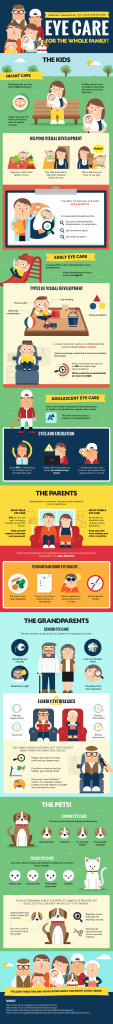

Vision loss is feared more than the loss of any other sense and is considered to affect the quality of life more than most other issues. When it comes to children, even partial vision loss can be damaging because it can affect the way that your child learns and develops. There are several different types of issues that may affect your child’s vision. Awareness is key to prevention and treatment.

Vision loss is feared more than the loss of any other sense and is considered to affect the quality of life more than most other issues. When it comes to children, even partial vision loss can be damaging because it can affect the way that your child learns and develops. There are several different types of issues that may affect your child’s vision. Awareness is key to prevention and treatment. Amanda Duffy

Amanda Duffy