What is primary congenital glaucoma?

Glaucoma in children includes a variety of disorders in which drainage system of the eye does not function adequately, leading to abnormally high pressure inside of the eye (the intraocular pressure, or IOP), and resulting in damage to many different structures of the child’s eye. If not treated promptly and successfully, pediatric glaucoma can lead to severe vision loss or even blindness in one or both eyes. In primary childhood glaucoma, the drainage system usually has not formed properly (often resulting from a genetic abnormality) while in secondary childhood glaucoma, the abnormal fluid outflow problem results from other problems with the eye(s), sometimes accompanied by other medical problems outside the eyes.

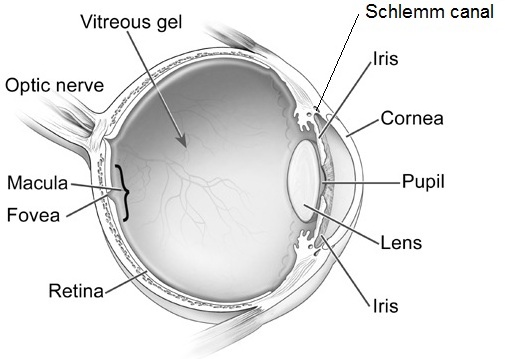

Primary congenital glaucoma is the most common of the primary childhood glaucoma types, although it is still rather rare. Let’s take a moment now to review the parts of the eye, and eye’s drainage system, sometimes also called the “aqueous outflow pathway”, since it drains the fluid within the eye (the aqueous humor), which is separate from the tears that flow on the outside of the eye’s surface and then into the nose or down a child’s cheeks.

The aqueous outflow pathway of the eye (comprising both the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm canal), situated at the junction (or “angle”) between the iris (the colored portion of the eye) and the sclera (the white part of the eye), has not formed correctly (Figure 1).

The aqueous humor therefore builds up within the front portion of the eye, causing abnormal elevation of the IOP.

In contrast to the eyes of adults and older children, the entire eye in infants and young children is distensible and the high IOP in primary congenital glaucoma often causes stretching and damage to several parts of the eye; this most often results in enlargement, clouding and scaring of the cornea (the front window of the eye) as well as severe nearsightedness, damage to the optic nerve, and resulting poor vision.

Primary congenital glaucoma (also called PCG) is almost always genetic, although usually there is no one else in the family with the condition. It is not related to anything that the parents did (or did not do) during the pregnancy or afterwards, and does not have any relationship to the baby’s sex or racial background. It occurs in about 1 every 10,000 to 20,000 births in western countries, but may be more common in certain populations of the world. Most babies with this disease are otherwise normal.

How is primary congenital glaucoma diagnosed?

Most cases present within six months of birth, with nearly 80% presenting before one year of age. In 70- 80 % of cases both eyes are affected. Most cases present for medical attention due to the size or cloudy appearance of the cornea in one or both eyes (Figure 2).

In cases where only one eye is affected, a difference in size can be seen between the two eyes and this sometimes brings the baby to the ophthalmologist (Figure 3).

The diagnosis of PCG is based on clinical findings and there are three classic signs that the child can present with:

- abnormal sensitivity or intolerance to light (photophobia)

- excessive blinking or squinting of the eyelids (blepharospasm)

- excessive tearing (epiphora)

The exam in clinic can be challenging for infants and young children and most require an exam under anesthesia, to allow detailed examination of the eye(s) that would not be possible in the clinic. Often the ophthalmologist will be able to follow the examination under anesthesia with the most appropriate surgery for the glaucoma, if surgery is indeed required.

How is primary congenital glaucoma treated?

PCG is almost always treated with surgery, although medications are often needed to help in addition to the surgery. Medications are very useful before initial surgery to help reduce the IOP and decrease the clouding of the cornea. In addition, medications may be recommended to keep the IOP to a safe level after surgery has been performed. If the IOP is not controlled successfully, or if damage has been substantial prior to diagnosis and treatment, PCG causes severe vision loss and can even cause blindness. Sometimes the damage from PCG is uneven between a child’s two eyes, leading to amblyopia (“lazy eye”) in the more severely affected size.

The initial surgical procedure of choice is usually aimed at opening the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm canal (the aqueous outflow pathway) of the affected eye(s). This so-called “angle surgery” can be performed either from inside of the eye (goniotomy) or externally (trabeculotomy), and may need to be repeated more than once in some cases.

If angle surgery fails, other procedures are available to allow the aqueous humor fluid to exit the eye (glaucoma drainage device or filtration surgery), or even to decrease the amount of fluid the eye makes (cycloablation procedures). For these more difficult procedures, the child is usually referred to an ophthalmic surgeon with expertise in treating childhood glaucoma.

What is the prognosis for children with primary congenital glaucoma?

While vision loss can be severe, prompt diagnosis and effective treatment and follow-up for children with PCG usually allows affected children to have best-corrected vision of at least 20/50 vision in their better-seeing eye. Children with PCG require continued careful follow-up and treatment their lifetime, and may require more than one surgery, eye drops, and spectacles.

Successful care for children with PCG takes a dedicated team including the family, ophthalmologist, teacher and community support, and the child him/herself.

10/1/15

Elena Bitrian, MD

Elena Bitrian, MD

Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology, Division of Glaucoma

Mayo Clinic

Sharon F Freedman, MD

Sharon F Freedman, MD

Professor of Ophthalmology and Pediatrics

Chief of Pediatric Ophthalmology

Duke Eye Center, Duke University