Receiving a diagnosis of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy or glaucoma can be a shock. Loved ones naturally want to help, but they don’t always know what to do or how to do it. Here are 3 tips for caregivers helping people with low vision.

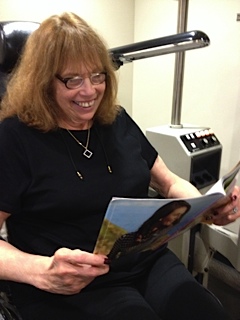

We asked vision-rehabilitation expert Maureen Duffy, CVRT, for advice. She suggests turning to local low-vision agencies, trained low-vision professionals and online resources, such as the Macular Degeneration Partnership and the VisionAware services guide. Perhaps most importantly, she says, look for a support group.

“I have found that most adults with whom I’ve worked turn to their peers, and they get the most guidance and help in vision-loss support groups,” says Duffy, an editor for Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, a writer and blog editor for VisionAware, and author of Making Life More Livable: Simple Adaptations for Living at Home After Vision Loss.

Duffy shared the three most important things to ask a loved one after they find out they have AMD:

1. What do you understand about what the doctor said and about what’s going on with your vision? What don’t you understand? What do we need to clear up?

If they don’t understand completely, ask if you can go to doctor with them to be a note-taker and information-gatherer. Ask the doctor for explanations. Be clear and concrete about the information you need — and ask the doctor for next steps.

The Macular Degeneration Partnership website has a downloadable list of questions to take along, as well as suggestions on how to be an advocate during a visit to the doctor on its “Be an Advocate” page.

2. What is the one thing you are most afraid of RIGHT NOW?

At first, their biggest fear is of going totally blind: “I won’t be able to do anything; I’ll be all alone; I’ll be totally helpless.” With AMD, they won’t go totally blind, and they can learn to make the most of their peripheral vision. There are services that can help, but it’s tough in the beginning: Go slowly.

Vision-rehabilitation services can help teach them to function safely and independently in critical day-today activities, such as:

• Independent movement and travel:

- getting around indoors

- walking with a guide

- using a long white cane

- crossing streets

- using public transportation

- using electronic travel devices

• Independent living and personal management:

- preparing meals

- managing money

- labeling medications

- making home repairs

- enjoying crafts and hobbies

- shopping

• Communication and technology:

- telling time with an adapted clock or watch

- signing their name

- using tablets and smartphones

- using computers with speech or screen magnification

- learning braille

3. What is the ONE thing you are most afraid you can’t do?

Don’t start talking about everything that may need to go on; it’s just too much and is overwhelming. Start with the one thing. “I can’t aim for the toilet”; “I can’t keep food on the fork”; “I can’t make my coffee in the morning.” Help them find solutions for simple things. Figure out alternatives. That little bit of accomplishment encourages self-analysis.

“Many people have difficulty telling currency bills apart,” Duffy says. She shares a simple, effective way to do this by folding each bill differently:

- Keep the $1 bill flat and unfolded.

- Fold the $5 bill in half crosswise (with the short ends together).

- Fold the $10 bill in half lengthwise (with the long sides together).

- Fold the $20 bill like a $10 bill lengthwise, and then in half again crosswise, like the $5 bill.

It’s important to remember that no matter how much you may want to help, your loved one may not be ready to accept assistance. Pushing too much too soon isn’t helpful. Once you ascertain that your loved one is ready to be receptive, offer your help gently, slowly and with empathy.

9/8/15

Maureen A. Duffy, CVRT

Maureen A. Duffy, CVRT

Social Media Specialist, visionaware.org

Associate Editor, Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness

Adjunct Faculty, Salus University/College of Education and Rehabilitation