In looking at the many articles we shared with you in 2015, we found that your interests were varied. From the science of vision, eye facts and eye disease to helpful suggestions to help your vision.

Here is the list of the top 10 articles you read last year. Do you have a favorite that is not on the list? Share it in the comments section below.

- Rods and Cones Give Us Color, Detail and Night Vision

- 20 Facts About the Amazing Eye

- Understanding and Treating Corneal Scratches and Abrasions

- 32 Facts About Animal Eyes

- 20 Facts About Eye Color and Blinking

- When You See Things That Aren’t There

- Posterior Vitreous Detachment

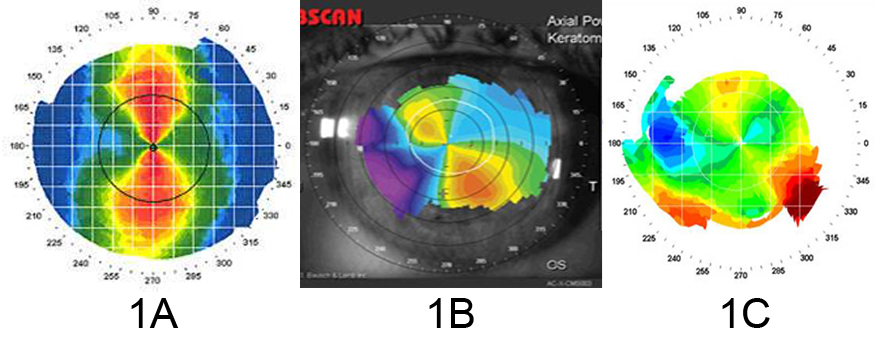

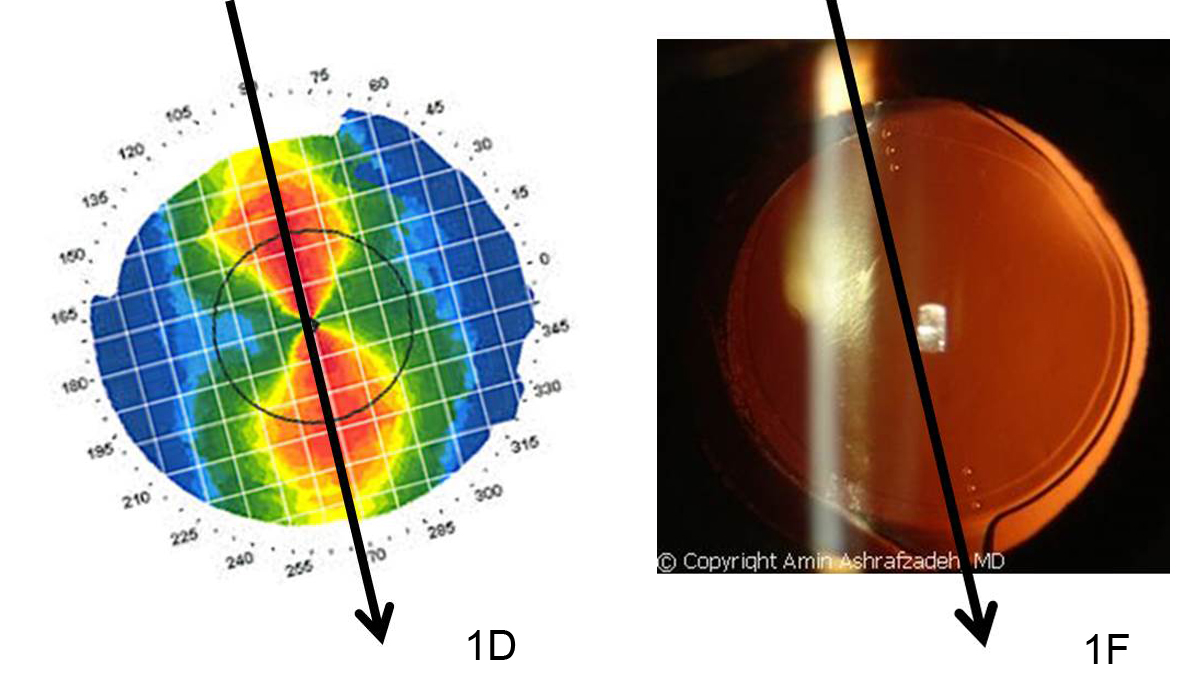

- Can Keratoconus Progression Be Predicted?

- Winter Weather and Your Eyes

- Coffee and Glaucoma: “1-2 cups of coffee is probably fine, but…”

Do you have any topics you would like to see discussed in the blog? Please leave any suggestions you might have in the comments below.

1/7/16

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Vice President of Development

Discovery Eye Foundation