8/5/14

For something different, and a little fun, here some interesting facts about animal eyes that you may not have known.

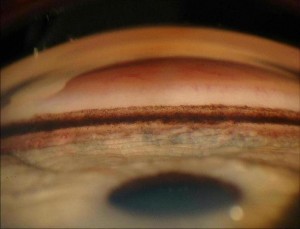

- Shark corneas are similar to human corneas, which is why they have been used in human transplants.

- A worm has no eyes at all.

- An owl can see a moving mouse more than 150 feet away.

- Guinea pigs are born with their eyes open!

- Scorpions can have as many as 12 eyes, but the box jellyfish has 24!

- Camels have three eyelids! This is to protect their eyes from sand blowing in the desert.

- Most hamsters only blink one eye at a time.

- Owls are the only bird which can see the color blue.

- Goats have rectangular pupils to give them a wide field of vision.

- A scallop has around 100 eyes around the edge of its shell to detect predators.

- Snakes have two sets of eyes – one set used to see, and the other to detect heat and movement. They also don’t have eyelids, just a thin membrane covering the eye.

- The four-eyed fish can see both above and below water at the same time.

- Owls cannot move their eyeballs – which has led to the distinctive way they turn their heads almost all the way around.

- A dragonfly has 30,000 lenses in its eyes, assisting them with motion detection and making them very difficult for predators to kill.

- Dolphins sleep with one eye open.

- The largest eye on the planet belongs to the Colossal Squid, and measures around 27cm across.

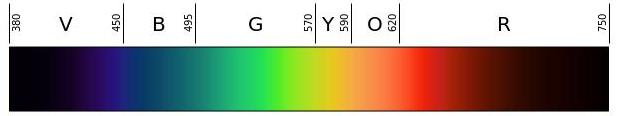

- Geckos can see colors around 350 times better than a human, even in dim lighting.

- The eyes of a chameleon are independent from each other, allowing it to look in two different directions at once.

- A camel’s eyelashes can measure up to 10cm long, to protect its eyelashes from blowing sand and debris in the desert.

- An ostrich’s eye is bigger than its brain.

- Dogs can’t distinguish between red and green.

- Polar bears have a third eyelid that helps filter UV light.

- Human eyes are not the most highly evolved. The mantis shrimp has four times as many color receptors as the human eye and some can see ultraviolet light.

- Pigeons can see millions of different hues, and have better color vision than most animals on earth.

- Cat’s eyes have almost 285 degrees of sight in three dimensions – ideal peripheral vision for hunting.

- Although color blind, cuttlefish can perceive light polarization, which enhances their perception of contrast.

- A moth’s eyes are covered with a water-repellant, anti-reflective coating.

- An ant only has two eyes, but each eye contains lots of smaller eyes, giving it a “compound eye.”

- Eagles have 1 million light-sensitive cells per square millimeter of the retina – humans only have 200,000.

- A honeybee’s eye is made of thousands of small lenses. A drone may have up to 8,600 and the queen be can have 3,000-4,000 lenses.

- The night vision of tigers is 6 times better than humans.

- Eyes on horses and zebras point sideways, giving them tremendous peripheral vision, to the point of almost being able to see behind them, but it also means they have a blind spot right in front of their noses.

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Vice President of Development

Discovery Eye Foundation