11/20/14

Defining Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is a group of metabolic disorders in which a person has high blood sugar levels. It occurs either because the pancreas does not produce enough insulin, or because the body does not respond appropriately to the insulin that is produced. Insulin is the hormone that converts sugar into energy for the body. There are several forms of diabetes.

Type 1 diabetes occurs when the pancreas does not produce adequate levels of insulin. It usually develops during childhood or adolescence; however, it can also occur in adults. Those with type 1 diabetes must take insulin injections. About 10 percent of those with diabetes have type 1.

Type 2 diabetes is the most common type of diabetes, affecting about 90 percent of those with diabetes. It is caused by the combination of the body’s resistance to insulin (not using its own insulin efficiently) and the pancreas not producing enough insulin. As a result, there is an increase in the level of sugar, or glucose, in the blood.

Gestational diabetes occurs in pregnant woman who have not previously had diabetes but whose blood sugars become elevated during pregnancy. In many patients, their blood sugars will return to normal after the pregnancy is over. Placental hormones make the mother resistant to insulin, causing a buildup of blood sugars. These women are at high risk for type 2 diabetes later on in their lives.

Diabetic Retinopathy: An Overview

Anyone with uncontrolled diabetes is at risk for developing diabetic retinopathy. According to the National Eye Institute, between 40 to 45 percent of Americans with diabetes have some form of diabetic retinopathy, the most common eye condition associated with diabetes.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports between 12,000 and 24,000 new cases of blindness each year due to diabetic retinopathy, making it the leading cause of vision loss among American adults, ages twenty to seventy-four. The Center also projects that by 2050, the number of Americans age forty and older with diabetic retinopathy will grow from a current 5 million individuals to about 16 million. Although these statistics are alarming, you can prevent or delay damage to your vision by controlling your diabetes, along with obtaining regular eye evaluations and treatment.

Defining Diabetic Retinopathy

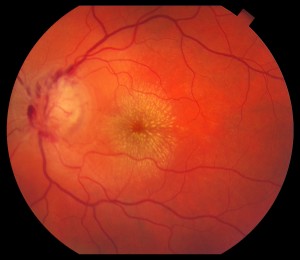

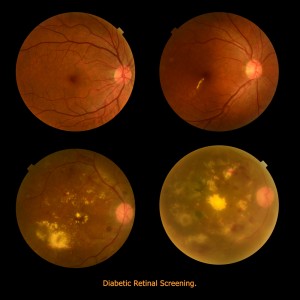

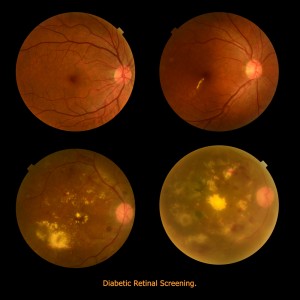

Diabetic retinopathy is a disease affecting the retina, caused by elevated blood sugar levels. It usually affects both eyes and occurs when uncontrolled blood sugar levels damage the small vessels of the retina, the light-sensitive tissue in the back of your eye. The retina is responsible for processing images that make vision possible. To produce clear, distortion-free vision, the retina must lie completely flat. If the delicate retinal tissue is damaged, images that you see may be blurred or distorted.

Diabetic retinopathy is a progressive disease, and thus worsens over time. Although some effects, such as blurriness and distortions, may be mild or subtle, the long-term consequences can cause severe vision loss.

Symptoms of Diabetic Retinopathy

Because diabetic retinopathy rarely causes pain, symptoms are not always apparent in the earliest stages. In fact, damage to your retina could be occurring long before you have noticeable signs. When symptoms do occur, they’re often caused by retinopathy affecting the macula, the area at the center of the retina. Symptoms may include the following:

• blurred vision

• seeing dark spots or “floaters” (small specs in your field of vision)

• decreased night vision

• vision loss

• problems seeing colors

It’s important that you see your eye specialist immediately if you have any such symptoms. Diabetic retinopathy cannot be cured, but with careful monitoring, it can be diagnosed and treated, before your vision is impaired. The treatment is typically less invasive and more effective when diagnosed at an earlier stage, before permanent damage has occurred.

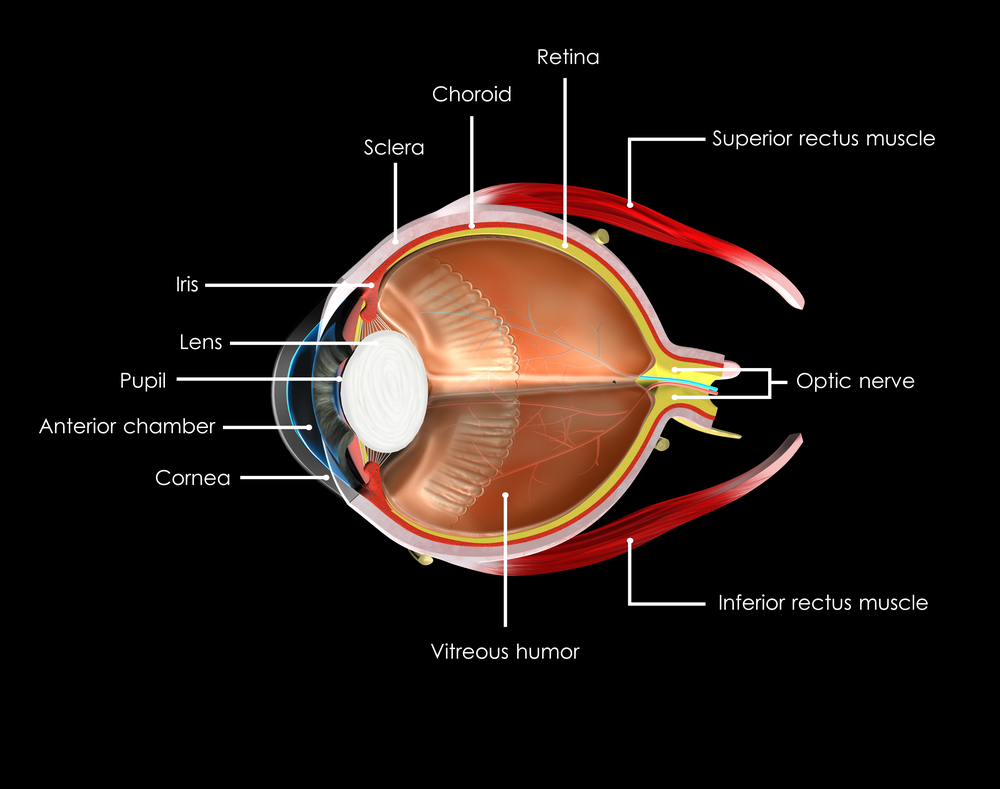

How the Retina Works

The retina is made up of specialized nerve tissue that contain microscopic receptors (called cones and rods) and other nerve cells that line the back of the eyeball.

These cells carry signals (images that we see) along the optic nerve to a special area of the brain, where they’re interpreted into what we perceive as sight. You might compare the retina to film in a camera—the film delivers the photo image that the camera captures.

There are two main areas of the retina that can be damaged by diabetic retinopathy:

• The macula, the center of the retina. The macula allows you to read and see fine details and recognize colors. At the very center of the macula is a dimple known as the fovea. It is the most sensitive portion of the macula and makes sharp vision possible.

• The peripheral retina, which is the portion of the retina that is outside the macula. It’s responsible for your side vision and also makes night vision possible.

The retina lies on a nutrient-rich flat “carpet” of vessels that nourish it with necessary oxygen and nutrients. To reach the retina, however, nutrients must pass through two buffers—a thin membrane called Bruch’s membrane and a single layer of specialized cells called the retinal pigment epithelium. Waste products are also transported away from the retina through these two membranes. Diabetic retinopathy can interfere with this constant import of necessary nutrients and export of waste products.

Risk Factors for Diabetic Retinopathy

There are many factors that can raise your risk for diabetic retinopathy. However, you’ll note that many of these risk factors can be controlled.

Duration of Diabetes and Glucose Control

The longer you’ve had poorly controlled blood glucose levels, the higher your risk for diabetic retinopathy. Most diabetic individuals develop eye problems overtime, making duration of their diabetes one of the strongest predictors that they will develop this eye disease. Research has shown that nearly all type 1 diabetics and 60 percent of type 2 diabetics develop the condition within the first two decades of their diabetes diagnosis.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends fasting glucose levels between 70 and 120 mg/dL and less than 180 mg/dL two hours after meals. They also recommend a hemoglobin A1c of 7 percent of less. Hemoglobin A1c is a protein in red blood cells that bonds with blood sugars. Since red blood cells can live from 90 to 120 days, the hemoglobin A1c stays in the blood for that length of time. Accordingly, it is effective in measuring the average blood sugars over a period of time. This test tells doctors how well your treatment plan is working. You should always know what your hemoglobin A1c values are, as they may affect the interval between your retinal examinations.

Obesity

The more fatty tissue you have, the more resistant your cells are to insulin. Obesity increases your risk for diabetes as well as other serious conditions such as heart disease. Estimates suggest that 65 percent of Americans may be overweight. Being overweight aggravates high blood pressure and cholesterol. Achieving a healthy weight is important in controlling blood sugars and diabetes related complications.

Lifestyle Choices

A sedentary lifestyle, especially if you are overweight, contributes to many diseases, including diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol levels. On the other hand, physical exercise improves circulation, lowers blood sugars, and improves your body’s use of insulin. This results in improved blood sugar levels. This benefit of increased sensitivity to insulin continues for hours after you stop exercising.

Exercise also promotes weight loss. A sedentary lifestyle contributes to insulin resistance, and makes it more difficult to keep weight off. Even light or moderate physical activity can help lower blood sugars.

Smoking is another major risk factor for developing diabetic retinopathy. Smoking also causes diabetic retinopathy to progress faster. The nicotine in tobacco not only contributes to higher blood pressure and higher cholesterol levels, but it also impairs insulin activity. Even though quitting can be difficult, it is critical to heart health and diabetes control.

Unlike smoking, alcohol consumption doesn’t have a direct influence on diabetic retinopathy. Yet because it can affect diabetes control, drinking in excess can affect the health of your eyes. Your doctor can tell you what constitutes drinking in moderation for you.

High Cholesterol Levels

Diabetes puts you at risk for chronically high cholesterol or blood fats that promote the buildup of plaque in your arteries. Although the tiniest vessels of the retina are too small for such build-up, uncontrolled cholesterol can contribute to macular edema and the development of hard exudates, the small yellow spots or lipid deposits that may form in the macula. Both conditions are associated with a higher risk of vision loss.

Doctors advise keeping “bad” or low density cholesterol (LDLs) less than 70 mg/dL. Good cholesterol or high density lipoproteins (HDLs) should be greater than 40 mg/dL in men and 50 mg/dL in women. Both men and women should strive for triglycerides, another type of fat, at levels less than 150.

High Blood Pressure

If you have both diabetes and high blood pressure (also called hypertension), you may be at higher risk for a number of eye-related problems, including retinopathy, glaucoma and optic nerve damage. Seriously elevated blood pressure not only stresses your heart, it also raises the risk for eye problems, particularly macular edema and bleeding. Chronic hypertension combined with long-term diabetes also increases the chance that your retinopathy will be more destructive and progress more rapidly. Research has consistently shown that keeping your blood pressure below 130/80 mmHg is important in minimizing the risk of hypertension related complications.

Race/Ethnicity

Diabetic retinopathy is more common in some ethnic and racial groups than others. African Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic/Latino Americans, American Indians and Alaskan Natives are at higher risk for type 2 diabetes than non-Hispanic whites.

African Americans and Mexicans are almost twice as likely as whites to have eye problems, according to the American Diabetes Association. Native Americans also have an increased for diabetic retinopathy. Researchers aren’t sure why some ethnic groups have higher rates of diabetes, which increase the risk for retinopathy and other problems.

Age and Gender

As mentioned earlier, the longer you have diabetes, the greater your risk for diabetic retinopathy. Not surprisingly, this complication is rare among children but common among older diabetic adults. A recent study by Prevent Blindness America and the National Eye Institute, demonstrated that older adult Americans are facing a bigger threat of all age-related eye diseases (diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, cataracts and open angle glaucoma) today than at any other time.

Genetics

Our genetic make up has an important effect on our predisposition for many health issues such as diabetes. Scientists believe that many genes or combinations of genes either promote diabetes in certain individuals or protect them from developing it.

Scientists have yet to identify every gene involved in type 1 and type 2 diabetes, but they have shown that genetics are a factor. Research studies of identical twins, for instance, have demonstrated that if one twin has type 1 diabetes, the other twin has a 50 percent change of developing the disease. If one twin has type 2 diabetes, the other twin has a 75 percent chance of developing it.

Pregnancy

Gestational diabetes is a type of diabetes linked to pregnancy; however, diabetic retinopathy is usually not a complication in these women. However, if you’re already a diabetic and become pregnant, you are at an increased risk of developing diabetic retinopathy. This is a result of the hormonal and metabolic changes that occur during pregnancy, making the disease and its complications progress more rapidly. It is recommended that you see a retinal specialist for evaluation and monitoring.

In Summary

• Diabetic retinopathy is a serious complication of diabetes that results from high glucose levels damaging the retinal blood vessels. This can cause loss of vision.

• Between 40 and 45 percent of diabetic Americans have some form of diabetic retinopathy.

• The earliest form of the disease is called background diabetic retinopathy. With time it progresses to mild, moderate, or severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy.

• Without proper diagnosis and treatment of nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, the condition can advance to proliferative diabetic retinopathy, which is a serious sight-threatening stage of the disease.

• Macular edema is due to build up of fluid and thickening of the macula and can occur with any type of diabetic retinopathy. It is the most common cause of vision loss in those with diabetes.

• The duration of your diabetes and how well blood glucose is controlled are major risk factors for the development and progression of diabetic retinopathy.

• Other risk factors that play a significant role in the development of retinopathy, include high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking.

• As an individual with diabetes, you’re also at increased risk for other eye diseases, especially glaucoma, cataracts, retinal vein occlusion and optic nerve damage.

• Good blood sugar control, regular eye examination, and timely treatment are the key factors in reducing the damage to the eye and keeping your vision.

Pouya N. Dayani, MD

Pouya N. Dayani, MD

Retina-Vitreous Associates Medical Group

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Susan DeRemer, CFRE