No one wants to loose their eyesight, so Keeping your eyes healthy is a number one priority. Here are the top 10 tips for saving your vision.

8/4/15

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Vice President of Development

Discovery Eye Foundation

No one wants to loose their eyesight, so Keeping your eyes healthy is a number one priority. Here are the top 10 tips for saving your vision.

8/4/15

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Vice President of Development

Discovery Eye Foundation

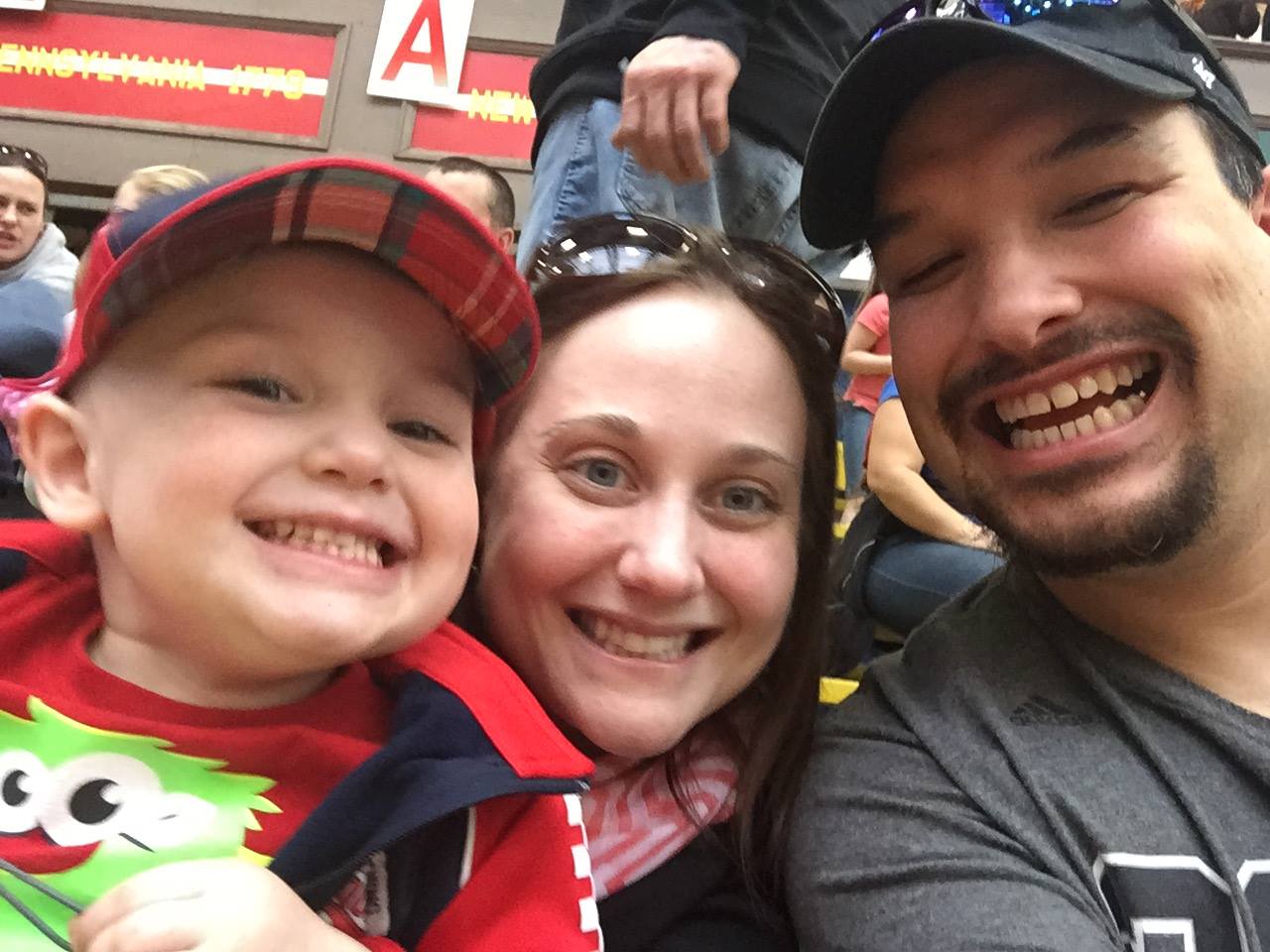

The stories that people share about their vision loss help remind everyone not to take your vision for granted. The following article is from the Keratoconus Group Blog, and is used with their permission. It reveals the emotional toll of keratoconus, while trying to find the most comfortable treatment option that will allow you to see.

My keratoconus story begins just as one major life event ended and another was just starting.

I finished my dissertation and successfully defended it in June of 2007 then set off across the country with my then girlfriend (now wife) to start new jobs. Everything was on the upswing and all appeared normal. However, it had been about a year since my last visit to the optometrist and being in a new place, I had to go through the dubious task of finding one.

I ended up getting an appointment with the optometrist at our local Walmart as I had broken my only pair of glasses and needed a quick replacement. The visit was going normal (or so I thought) until he came back into the exam room after checking on something. It was with a grave expression that he told me that he noted some concerning findings and I should probably speak with someone who had more experience with keratoconus.

For the next hour or so, I was in a panic that I was going blind. That is until I got online to get more details on what this was all about. After reading into the late evening, a great many eye-related issues over the past several years suddenly made sense. I immediately recalled my many complaints about my night time driving becoming more bothersome because oncoming headlights were blinding. It was on the many forums where I first learned of the terms halos and ghosting, which I would become all too familiar with in subsequent years. Lastly, I had tried to switch from glasses to soft contact lenses roughly a year before my move and was not able to do it. I didn’t know it then but my left contact kept sliding off because of my enlarged cone. In retrospect, I still cannot fathom how my optometrist did not recognize the symptoms.

After a little research, I found a local optometrist who had experience with KC. He basically wanted to put me in RGP lenses and call it a day. This was a horrible experience and I will save everyone the gory details. Suffice it to say, I would stay in glasses until February of this year–nearly 7.5 years since my initial diagnosis.

Little by little I was becoming aware that my vision was getting worse. Night time driving was becoming near impossible, reading on the computer (which is a huge bulk of my job) was increasingly difficult and the photophobia was simply impossible to ignore–especially at stores and restaurants that used brutal florescent lighting. I did have tomography scans done yearly and thankfully the progression was slow, but it was still progression. Something had to change.

After leaving my optometrist for several philosophical reasons, I was able to find a group outside of my area, but still within driving distance, who were expert with patients with KC. It was there that I learned about scleral lenses and how they could be of benefit. My ophthalmologist and I also discussed cross-linking, but decided that since FDA approval is around the corner, we have the luxury of time to wait. However, he strongly encouraged me to switch to the scleral lenses.

I am ever thankful that he did. My life, in just a few short weeks, has been irrevocably changed. We are still working out the fine tuning, but the vision restored is unbelievable. I never thought I would see this well again. Overall, vision is 20/25 and I’ve also noted that my peripheral vision is back to normal. Also, and most thankfully, my night time vision and ability to drive safely have been restored. It is still unbelievable what these lenses have done for me and my overall quality of life.

There is the old cliché that you don’t know what you have until it is lost. I am still amazed how I didn’t truly realize how bad my vision had gotten until I got the sclerals. For those with KC and are on the fence as to how best to deal with it, please don’t hesitate to talk with your doctor to find the best solution for you.

7/30/15

Reading the small print can be very challenging as you age. Your eyes lose their elasticity due to a hardening of the lens inside your eye. This condition is called presbyopia and begins to affect many people after the age of 40, continuing to advance as you age. Readers glasses or a single prescription is no longer the best solution. You may find that you need one pair of eyeglasses for reading a book that you hold in your lap, while a different strength may be needed to use a computer at your desk, because it is further away. But it is not just the font size that can affect how easily you can read. Font shape, spacing and color all contribute to readability. Here are some helpful hints if you are producing printed materials for people over 40.

Print Size

Ideal size will vary depending on the font you choose as not all fonts are the same size. A 14 point type size in New Times Roman is smaller than a 14 point Verdana font. Therefore smaller fonts should not be less than 14 points and you may find they are easier to read at 16 points.

Font Type

Decorative fonts are difficult to read and should be used sparingly. For the body of text stick to a regular font that is bolder, with thick lines that are more legible.

Some people prefer a serif font, such as Times New Roman, as they say it is easier to read because of the “tails” at the end of the letters that create an illusionary line, helping to guide the eye along the line. However, others prefer a sans serif font, such as Ariel. It can be easier to read because of the simplicity of the lines. It is a personal choice.

Regardless of the font you select, use both upper and lower case letters in your body text. All capitals letters can be difficult to read. Save them for headlines or to emphasize a word or two.

Avoid using italicized text as the letters appear squeezed together, increasing the reading difficulty.

Presentation Style

Allow for white space as it provides natural places for the eyes to relax and can help you focus on what you are reading.

Align text to the left, as it is easier to read. And don’t wrap text around graphics.

Keep normal spacing between letters, neither expanding nor condensing them which make it more difficult to read the words. Space lines of text at 1.5 instead of single space, to make the lines of text much easier to follow.

Contrast & Color

As you get older, yellow, blue and green become increasing difficult to differentiate from each other if they are used in close proximity to each other, especially if you have cataracts. Yellow can almost disappear.

To make it easier for reading, stick with very dark type on a white background. Avoid patterned backgrounds.

Avoid using very glossy paper as it creates glare that can make reading hard. Also make sure your paper is thick enough so print form the other side of the page cannot be seen.

Websites & Blogs

Most of the rules listed above for printed materials also apply to websites and blogs (expect the glossy paper rule). But here are a few additional suggestions for online communications.

Use design templates that are one column (or one and a sidebar) to make it easier read. This is especially true for viewing on mobile devices, even if your web design is mobile responsive.

Allow enough space around clickable items, such as word links and buttons, so they are easy to target and click separately. Make sure the linked text is clearly defined with a color that is easy to differentiate for the surrounding text. Bright royal blue is the most common color used.

Provide a space between paragraphs.

Online a sans serif font is much easier to read, but keep the size at 12 -14 points. Ariel is common font, but Tahoma and Verdana are often used and were specifically designed for online usage. Verdana is a naturally large font, so a 12 point can work well.

Offer a feature where you can easily change the size of the font directly from the screen. An example is the Discovery Eye Foundation site where the control is located at the top right of the page. You can even offer on-screen contrast settings like on the Macular Degeneration Partnership page, at the top center of the page.

Avoid layering shades of the same color, such as dark blue type on a light blue background. Also avoid layering colors that clash such as red type in a purple block. These make reading the text more difficult.

These are just a few of the ways to make text easier to read, both in print and online. Do you have any other tips to share below in the comments?

7/28/15

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Vice President of Development

Discovery Eye Foundation

Corneal transplants can be very successful at replacing diseased or damaged corneas. However, vision after a corneal transplant is often limited by high amounts of astigmatism. Treating this astigmatism is often difficult. Typically the amount of astigmatism is higher than can be corrected with glasses. Rigid contact lenses are often required. LASIK, PRK and astigmatic incisions in the cornea (astigmatic keratotomy) have all been tried with varying success.

This month, doctors at the Gavin Herbert Eye Institute at the University of California, Irvine, published a paper describing the use of commercially available, FDA approved toric (astigmatism correcting) intraocular lenses (IOL) during cataract surgery in patients with previous corneal transplant surgery.

Good candidates for this procedure are those who have had all transplant sutures removed and had corneal astigmatism that was stable, and for the most part symmetric and regular. (Image 1A shows topography that is both regular and symmetric. Image 1B is regular but not symmetric and image 1C is irregular.)

The study showed improvement in uncorrected vision (post-treatment average 20/40) and vision corrected with glasses only (post-treatment average 20/25). The images below, 1D and 1F, illustrate how toric intraocular lenses are positioned along the axis of corneal astigmatism.

While any intraocular surgery after corneal transplant can decrease the life expectancy of the graft, no complications or graft failures were seen during the course of the study. Not all types of astigmatism can be treated with this procedure.

This study highlights an effective treatment for regular symmetric corneal astigmatism after corneal transplant in patients needing cataract surgery.

7/24/15

Matthew Wade, MD

Matthew Wade, MD

Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology

Gavin Herbert Eye Institute

University of California, Irvine

Vision is something we take for granted, but when we start to have trouble seeing it is easy to panic. This blog has covered a variety of eye issues for every age, from children through older adults. Here are a few articles from leading doctors and specialists that you may have missed and might be of interest.

Bill Takeshita, OD, FAAO – Visual Aids and Techniques When Traveling

Michelle Moore, CHHC – The Best Nutrition for Older Adults

Arthur B. Epstein, OD, FAAO – Understanding and Treating Corneal Scratches and Abrasions

The National Eye Health Education Program (NEHEP) – Low Vision Awareness

Maintaining Healthy Vision

Sandra Young, OD – GMO and the Nutritional Content of Food

S. Barry Eiden, OD, FAAO – Selecting Your Best Vision Correction Options

Suber S. Huang, MD, MBA – It’s All About ME – What to Know About Macular Edema

Jun Lin, MD, PhD and James Tsai, MD, MBA – The Optic Nerve And Its Visual Link To The Brain

Ronald N. Gaster, MD FACS – Do You Have a Pterygium?

Anthony B. Nesburn, MD, FACS – Three Generations of Saving Vision

Chantal Boisvert, OD, MD – Vision and Special Needs Children

Judith Delgado – Driving and Age-Related Macular Degeneration

David L. Kading OD, FAAO and Charissa Young – Itchy Eyes? It Must Be Allergy Season

Lauren Hauptman – Traveling With Low Or No Vision / Must Love Dogs, Traveling with Guide Dogs / Coping With Retinitis Pigmentosa

Kate Steit – Living Well With Low Vision Online Courses

Bezalel Schendowich, OD – What Are Scleral Contact Lenses?

In addition here are few other topics you might find of interest, including some infographics and delicious recipes.

Pupils Respond to More Than Light

10 Tips for Healthy Eyes (infographic)

The Need For Medical Research Funding

Protective Eyewear for Home, Garden & Sports

7 Spring Fruits and Vegetables (with some great recipes)

6 Ways Women Can Stop Vision Loss

6 Signs of Eye Disease (infographic)

How to Help a Blind or Visually Impaired Person with Mobility

Your Comprehensive Eye Exam (infographic)

Famous People with Vision Loss – Part I

Famous People with Vision Loss – Part II

Development of Eyeglasses Timeline (infographic)

What eye topics do you want to learn about? Please let us know in the comments section below.

7/21/15

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Vice President of Development

Discovery Eye Foundation

“I’m worried about my mother”, Janet said. “Lately, she’s been telling me that she sees things that aren’t there – bugs, flowers, faces floating in the air! Is she getting Alzheimers?! She’s healthy and has always been sharp as a tack, although she has macular degeneration. What should I do? Yesterday, she said some children were playing in her yard but there was no one there!”

Janet’s mom probably has Charles Bonnet Syndrome (CBS) which can affect anyone with a severe vision loss. People with CBS see things that are not there but they know they are not real.

They have reported a wide variety of images, including bugs, flowers, animals, people, trees, houses, balloons and patterns. In Dr. Lylas Mogk’s excellent book on macular degeneration, she describes a patient who saw monkeys wearing clothes, playing in the trees. Another person saw an entire dinner party in her dining room!

One study documented that 80% of the participants saw people; 38% saw animals. Children and groups of people were also common. Twenty-seven percent had them daily. For some people, the images lasted less than a minute, but for 53%, they continued for one minute to one hour.

The images come and go and are usually interesting or amusing and not threatening. Dr.Mogk states, “One of the most remarkable qualities of these figures is that they almost always wear pleasant expressions and often make eye contact with the viewer. Menacing behavior, grotesque shapes, and scenes of violent conflict are not, to my knowledge, a part of this syndrome.”

The same images usually repeat themselves – often at the same time of day. They may happen daily or infrequently. The person with CBS knows that they are not real, and is fully awake when they occur. In the study, 82% of people immediately knew that the images were not real. The rest were deceived only briefly and then because the images were such common objects.

The images don’t block out what is behind them and they don’t have any sound associated with them. They’re usually in color, but can be in black and white. They are very detailed – much more detailed than what the patient with macular degeneration can usually see. People may see anything and the images are usually not anything they’ve seen in real life; they don’t seem to be visual memories. We don’t know exactly why this happens; it may be that the brain is trying to show something in the absence of normal visual impulses.

Like “phantom limb syndrome”, the body experiences things that are not there. Between 10% and 21% of people with low vision experience CBS, but some studies put the number higher than 40%.

On a positive note, patients do report that the hallucinations are reduced over time and eventually go away completely. At a recent support group meeting, one participant mentioned that hers had disappeared and wryly admitted that she missed them! She’d gotten used to them and they didn’t interfere with her daily life after a while.

A research study in the Netherlands found that people used a variety of techniques that were helpful, in addition to the ideas above.

Thousands of people live with Charles Bonnet Syndrome and manage quite well – you are not alone!

One note of importance: If the experience does not seem to meet the description of Charles Bonnet Syndrome, further testing may be necessary. Other medical conditions can trigger hallucinations, such as Parkinson’s. A full neurological work-up is indicated if the images are frightening, threatening or are accompanied by sounds or bizarre sensations.

This article is from the NEW Macular Degeneration Partnership website – AMD.org. If you enjoyed it, please check out other articles related to age-related macular degeneration and sign-up for the monthly AMD E-Updates.

References:

Judith Delgado

Judith Delgado

Executive Director

Macular Degeneration Partnership

A Program of Discovery Eye Foundation

Vision, while it is important to humans to carry out daily tasks, is a matter of life and death to animals in the wild. Predators need powerful, accurate vision to stalk their targets, while prey animals have developed a wide field of vision that is sensitive to movement, alerting them of danger. For each animal, their vision is a product of their environment and may have evolved over time. Here are some animals with unique eyes.

The tarsier is a small mammal about the size of a squirrel with eyes that are the largest of any mammal relative to body size, and weighing more than its brain. For a human to have eyes in the same proportion to body size, our eyes would be the size of grapefruits! The other unusual thing about a tarsier’s eyes is that they do NOT rotate in the eye socket. The tarsier must use his very flexible neck to rotate his head 180 degrees to see around him. He has great night vision, but very poor color vision, which is common with most nocturnal animals.

Another animal with relatively large fixed eyes is the owl. He also has a layer of tissue in the eye called the tapetum lucidum. This tissue is commonly found in nocturnal animals and deep sea animals in the back of the eye immediately behind the retina. It reflects visible light back through the retina, increasing the light available to see. Also because the eyes are fixed, owls can rotate their heads up to 270 degrees in both directions and 90 degrees vertically to look around.

A chameleon’s eyelids are fused, covering almost the entire eyeball except for the pupil. What is more unique is that the eyes work independently of each other and the chameleon can process the completely different images at the same time. However, when the chameleon spots potential prey, it focuses both eyes in the same direction, using stereoscopic vision for precise distance and depth perception. They have a full 360 degree field of vision and can see ultraviolet light.

Goats, along with most other hooved animals, have horizontal rectangular pupils. These pupils give them a field of vision of 320-340 degrees. Because of the special shape and large size of these pupils, the goat is able to have more control on how much light enters the eye, so they can see more easily at night.

Dragonflies have compound eyes that almost cover their heads and give them a full 360 degree filed of vision. The large part of their eyes is made up of 30,000 visual units called ommatidia (a cluster of light-sensing photoreceptor cells with a lens).  This gives them very acute vision, even in low light. What makes their vision even more remarkable is that they also have three smaller eyes call ocelli which can detect movement faster than the larger eyes, sending the information to the dragonfly’s motor center allowing for spilt second reaction times.

This gives them very acute vision, even in low light. What makes their vision even more remarkable is that they also have three smaller eyes call ocelli which can detect movement faster than the larger eyes, sending the information to the dragonfly’s motor center allowing for spilt second reaction times.

One of the most unusual eyes is that of the leaf-tailed gecko. The pupils are vertical with a series of “pinholes” that widen at night, allowing as much light as possible into the eye. Since they also have a more photoreceptor cells than most animals, they have incredible night vision. The eyes also have a series of intricate eye patterns to help with camouflage since there is no eyelid. Their eyes are protected by a transparent membrane, which they clean with their tongues.

Cats such as lions, tigers jaguars and leopards have extremely sharp night vision due to the fact they have the tapetum lucidum reflective tissue and far more rods (the light sensors of the eye) than cones (the color sensors of the eye) in their eyes compared to humans. However, because of the reduced number of cones, they can only distinguish a very limited range of colors.

The mantis shrimp has compound eyes like the dragonfly but with only 10,000 ommatidia per eye. However, each row of ommatidia has a particular function – some are for detecting light, others for detecting colors, etc. Mantis shrimp (who are not actually shrimp) have remarkable color vision with 12 types of color receptors (humans have three) as well as ultraviolet, infrared and polarized light vision. This means they have the most complex eyesight of any animal. Each of the manits shrimp’s eyes sit at the end of stalks allowing them to move independently from each other and the ability to rotate up to 70 degrees. Finally, unlike humans, the visual information is processed by the eyes themselves instead of the brain.

While the tarsier has the largest eyes relative to its size, the colossal squid has the largest eyes in the animal kingdom. Each of the colossal squid’s eyes can be as large as a foot in diameter. These exceptionally large eyes allow them to see well in dim light conditions, 2000 meters below the ocean surface. Also each eye has a built-in “flashlight” which can produce light so that whenever the squid focuses it eyes to the front, there is enough light for it to see its prey in the dark.

These are just a few of the animals with varied and unique vision. If you know of any others, please share them in the comments section below.

7/14/15

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Susan DeRemer, CFRE

Vice President of Development

Discovery Eye Foundation

Overview

People of all ages often view driving as the key to independence. Individuals with vision loss are no exception. Three groups of people with vision loss who wish to acquire or maintain the privilege of driving include teenagers with a congenital or acquired visual impairment who have never driven, adults with the same who have never driven, and adults with an acquired visual impairment who have driven in the past but may lose their license because of their vision loss.  However, vision standards for driving vary from state to state, and this variation persists despite decades of research demonstrating that there is no absolute cutoff criteria in visual acuity or peripheral vision for safe versus unsafe driving. The fact that states have variable standards results in people with visual impairments not being able to be licensed in some states, including perhaps their own, while being able to be licensed in a neighboring state. Clearly, the ability of these individuals to safely operate a motor vehicle does not change when they cross a state line. Yet, to maintain at least some driving privileges, they may find themselves having to move to a different state.

However, vision standards for driving vary from state to state, and this variation persists despite decades of research demonstrating that there is no absolute cutoff criteria in visual acuity or peripheral vision for safe versus unsafe driving. The fact that states have variable standards results in people with visual impairments not being able to be licensed in some states, including perhaps their own, while being able to be licensed in a neighboring state. Clearly, the ability of these individuals to safely operate a motor vehicle does not change when they cross a state line. Yet, to maintain at least some driving privileges, they may find themselves having to move to a different state.

It is well known that many older drivers modify their driving norms to help keep themselves and others safe. For example, many older drivers voluntarily reduce or stop driving at night, in hazardous weather conditions, or on super highways. By limiting their driving, older drivers, particularly those with visual impairments, are able to continue operating their automobiles safely and efficiently in spite of reduced vision. This is important, considering the vast majority of older adults live in the suburbs or in rural areas where automobiles are required for transportation.

Maximizing Visual Capabilities

It is important for all individuals, but particularly for drivers who are visually impaired, to make sure their spectacle correction is up-to-date. Contrast enhancement and glare control with filtering lenses can also be of great benefit. Most drivers have experienced driving into the glare of the sun, while looking through a dirty windshield. Although wearing sunglasses and keeping windshields clean is not mandatory, they certainly help drivers see more easily and feel more comfortable when driving.

Maximizing Visual Attention

Human factors research has found that inattention blindness and the cost of switching contribute to or directly cause automobile mishaps. Inattention blindness refers to when a person’s attention to one activity undermines his or her attention to other activities. For example, when drivers focus on directional signs, their attention is not on what is happening on the road in front of them. The cost of switching refers to the time it takes a person to switch attention between different activities. A common example that causes driving mishaps is when drivers text while driving. When people focus on texting while driving, their response to the traffic around them is delayed.

Useful Field of View testing research has shown that the time it takes a person to process visual information, especially the complicated visual environment experienced each time a person drives, increases with age. With this in mind, decreasing or eliminating the time it takes older drivers or drivers with visual impairments to look for and visually process signage should help them maintain their concentration on the road ahead and the traffic around them.

A simple way to reduce or eliminate the need to look for directional signage is with the use of a Global Positioning System (GPS) device that uses spoken directions. Older drivers and drivers with visual impairments in particular should consider using a GPS device with spoken directions so that they are freed from the distraction of looking for/at road signs and can keep their attention on the traffic around them.

Finally, with the technology, such as adaptive cruise control and lane alert warnings, currently available in cars, it is expected that all drivers will be safer behind the wheel.

Final Considerations

A good driver is someone who has the ability to perceive change in a rapidly changing environment; the mental ability to judge and react to this information quickly and appropriately; and the motor ability to execute these decisions, along with the compensatory skills to compensate for some loss of ability in the other areas. Additionally, a driver’s familiarity with the driving environment and his or her past driving record should be taken into account when considering limiting driving activities or retiring from driving altogether.

For many drivers with vision loss, a limited driver’s license that allows them to drive during daylight hours, within a restricted radius of their home, and at lower rates of speed may be all they desire. However, there are times when an individual will need to retire from driving altogether because of vision loss or a combination of vision and cognitive changes. When this time comes, the individual needs to understand that retiring from driving is for his or her safety and the safety of others.

Finally, it is well known that vision loss in general, as well as the loss of driving privileges, can lead to feelings of hopelessness and depression. Fortunately, there are many things that can enhance the functional abilities of individuals with vision loss. To learn about available resources for individuals with vision loss, visit the National Eye Health Education Program low vision program page at www.nei.nih.gov/nehep/programs/lowvision.

7/9/15

Mark Wilkinson, OD

Mark Wilkinson, OD

University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine

Chair of the National Eye Health Education Program Low Vision Subcommittee

Growing up in Los Angeles, Leah Bernstein always loved movies and made it her goal to work in the entertainment industry. She took typing, shorthand and bookkeeping in school, and when she was turned 16, her sister’s friend got her a job working from 5 pm to midnight at MGM Studios.

“I made enough money at MGM to go to Woodbury’s Business College and become an executive secretary,” she says. She spent the rest of her career working with entertainment-industry executives, including Irving Fein, who managed Jack Benny; renowned animator Ralph Bakshi; and producer/director Stanley Kramer, who was best known for The Defiant Ones, Judgment at Nuremberg, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. She worked with Kramer on 28 films, counting luminaries such as Sidney Poitier, Bobby Darin and Vivien Leigh among her friends, before she retired at age 69.

Since then, Bernstein spends time with her eight great-great nieces and nephews and has been a dedicated volunteer for organizations such as Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Beverly Hills Public Library, where she regularly attends the Macular Degeneration Partnership’s monthly support group.

“I go to the meetings every month; I like to hear what other people are going through,” she says. “Mostly, though, I love hearing about the latest research. I would like to improve my eyesight, and I’m hoping they will come up with eye drops for my dry eyes.”

Bernstein started wearing glasses in her early 40s, and since being diagnosed with age-related macular degeneration, she’s had cataract surgery in both eyes. “That didn’t help, but I do take the vitamins given to me by my retina doctor twice a day. I’m hoping those might be keeping my macular degeneration from getting worse,” she says.

She’s given up driving and now lives in an assisted-living facility, where she really hates the food. She has a little computer “for looking things up,” and she gets by with two pairs of glasses and a magnifier for reading.

“I wish I could read better. I really wish my eyes were better,” Bernstein says. “I do watch television. I see it — not as you see it — but I can see it with my distance glasses. And of course, I watch movies on my DVD player.”

7/7/15

Scleral Contact Lenses have taken over a century to evolve into one of the best options for managing eye diseases such as keratoconus. This evolution began in the late 1800’s, with blown glass lenses. However, until the advent of highly oxygen permeable plastics, scleral lenses had very limited application. Now, with current technology and materials, scleral lenses have become a mainstream and rapidly growing lens option.

Scleral lenses are becoming more popular due to the exceptional comfort they can provide even to the most unusual eye shape. This comfort is attributable to their large size that allows them to tuck behind the eyelids, their relative lack of movement with eye blinks, and their fluid reservoir that keeps the cornea hydrated and does not actually touch the fragile corneal tissue in individuals with keratoconus.

As utilization of and demand for scleral lenses began to grow last decade, it became apparent that there was a need for more professionals trained in fitting scleral lenses, as well as someone to provide a consensus opinion for the eye care world on what the standard of care should be for these lenses. In addition, a process for providing a credential for those that attained a level of expertise in scleral lens fitting would allow those seeking experts in the field of fitting sclerals to find an experienced professional.

The Scleral Lens Education Society (SLS) was established in 2009 as an organization to help bring professional consensus to the suddenly rapidly growing area of scleral lenses. The mission statement of the SLS reads: “The Scleral Lens Education Society (SLS) is a non-profit organization 501(c)(3) committed to teaching contact lens practitioners the science and art of fitting all designs of scleral contact lenses for the purpose of managing corneal irregularity and ocular surface disease. SLS supports public education that highlights the benefits and availability of scleral contact lenses.”

Beginning with the founding board which included world renown experts in scleral lens fitting such as Greg DeNaeyer, OD, Christine Sindt, OD, and Bruce Baldwin, OD, PhD, the SLS has worked to spread the word about the potential benefits of scleral lens wear to both providers and patients alike. Professional education has included scleral lens webinars, workshops, and lecture series that are always standing room only events.

Currently, the SLS has over 2000 member contact lens practitioners as well as over 50 fellows, or certified scleral lens fitters that have demonstrated their expertise through a peer reviewed process of case reports, publications, and lectures. Many of these members and fellows are international, with SLS fellows from 11 countries, 5 different continents, and 20 different states in the US. Members hail from all 50 states, 6 continents, and over 40 countries.

In addition, the SLS has numerous industry sponsors that support the mission of the society to provide patient access to experienced fitters across the world. The sponsors provide the resources that allow the educational opportunities for practitioners as well as the website and patient resources that are available.

SLS board members are elected to serve in various capacities, including fellowship, public education, and international relations, and are elected to one year terms. The current board consists of:

President, Muriel Schornack, OD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

Vice President, Melissa Barnett, OD, University of California, Davis

Secretary, Michael Lipson, OD, University of Michigan

Treasurer, Mindy Toabe, OD, Metrohealth, Cleveland, OH

Immediate Past President, Jason Jedlicka, OD, Indiana University

Fellowship Chair, Pam Satjawatcharaphong, OD, University of California, Berkeley

Public Education Chair, Stephanie Woo, OD, Havasu Eye Center, Lake Havasu, AZ

International Chair, Langis Michaud, OD, University of Montreal

For more information about scleral lenses and the Scleral Lens Education Society, please visit the website at www.sclerallens.org. If you or someone you know might benefit from scleral lenses, you can locate a fitter in your area through the website as well. If you are unable to locate a fitter near you on the website, please contact the SLS and we will try to locate options in your local area.

7/2/15

Jason Jedlicka, OD

Jason Jedlicka, OD

Clinical Associate Professor, Chief of Cornea and Contact Lens Service

Indiana University, School of Optometry