As covered earlier by Dr. Wade, the symptoms of dry eye disease (DED) can be variable. Simply put, dry eyes can be separated into two categories: aqueous tear deficient (ATD) or dysfunctional tear syndrome (DTS). More commonly there is a combination of the two that I like to refer to as ocular surface disease (OSD). Lucky for you, as clinicians, we have several tools that will allow us determine what type of DED you have.

Steps In A Dry Eye Diagnosis

First is a review of your symptomatology. This is crucial to determining if you 1) have DED, and 2) what type you have. This determination can drive our treatment plan that is individual to you. In addition, we utilize various questionnaires that can help us hone in on your OSD.

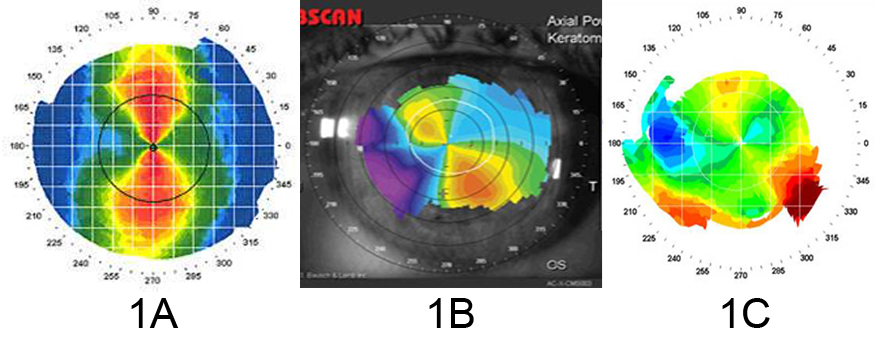

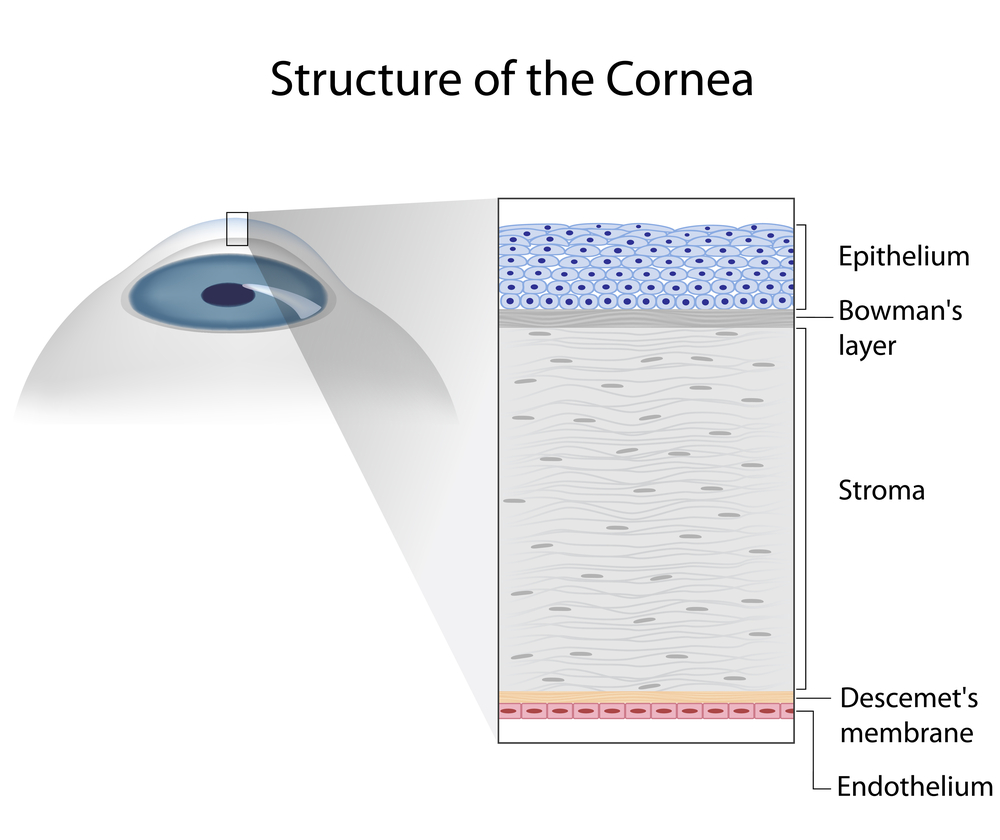

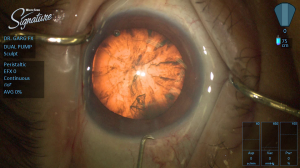

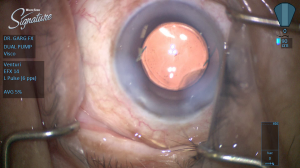

Second is the ocular examination. We use a microscope (slit-lamp) to carefully examine the surface of the eye. When we look at your tear film we are looking to see the amount and health of your tears, how well they are working, and what effect they are having on the ocular surface (conjunctiva and cornea). Not only do we look at your tears, but we pay special attention to your eyelids. In your eyelids, there are oil producing glands called Meibomian Glands. These glands are responsible for creating a key component to the tear film: lipid. Human tears are very complex, but simply put, tears have 3 main components – water, mucus, and oil. I like to describe tears like salad dressing. In order to have tasty salad dressing, there needs to be a balance of oil, vinegar, and spices. Human tears are very much similar. In order for your tears to work properly, There needs to be the proper balance of the aqueous component (water), lipid component (from the Meibomian glands), and mucus component (image 1).

If there is an imbalance in your tears, this will reflect in their function, and ultimately cause signs and symptoms of ocular surface disease. To highlight the appearance and function of the tears on the ocular surface, clinicians often use special stains that can aid us in determining the amount and function of your tears. Two of the most common stains are fluorescein and lissamine green. Each of these stains has particular characteristics that help determine the severity and extent of your ocular surface disease. For example, if you have significant staining near the bottom part of your cornea, your eyes maybe slightly open when you sleep, and therefore you may benefit from using an ointment at nighttime. Alternatively, if your tears appear to break up very quickly on your ocular surface, there is likely an imbalance in the tear composition that may benefit from institution of warm compresses along with tear replacement in the form of artificial tears.

Third is the use of ancillary testing to help confirm our clinical diagnosis. We are fortunate to have access to several commercially available OSD diagnostics at the Gavin Herbert Eye Institute. A brief description of if you have these diagnostics follows.

- 1) Schrimer Testing – This is a very simple and common method of determining whether a patient has hey aqueous tear deficiency. Essentially, the eye is numbed and a sterile piece of special paper is placed in the lower outer corner of the eye. After a specified amount of time, the amount of tears is recorded, and if under a threshold value (generally 10 millimeters at five minutes) there is a high suspicion of aqueous tear deficiency. Treatments for this subtype of OSD will be covered in the next blog.

- 2) Tear osmolarity – The most available tear osmolarity system is from TearLab. With this test, we look at the integrity of the tears by determining the osmolarity – essentially the ultrastucture of the tears. If the tear osmolarity is high (hyperosmolar), we know that the tears are not functioning properly. With proper institution of treatment, the osmolarity can normalize indicating a healthier tear film. This test is very noninvasive, requiring only a tear sample of 50 nanoliters – less than the volume of a single tear!

- 3) InflammaDry – Inflammation has long been accepted as a hallmark of dry eye disease/ocular surface disease. As such, many of our treatment modalities have focused on treating ocular surface inflammation (discussed in the next installment of this blog). Prior to having access to the InflammaDry test, we would have to assume that there was inflammation involved in an individual’s OSD. Now, however, we can test the ocular surface for inflammatory markers and have an answer within just a few minutes. This test not only allows us to custom tailor treatments to an individual, but also we are able to see if our treatments are working. Again, this test is minimally invasive requiring the small sample of tears for testing.

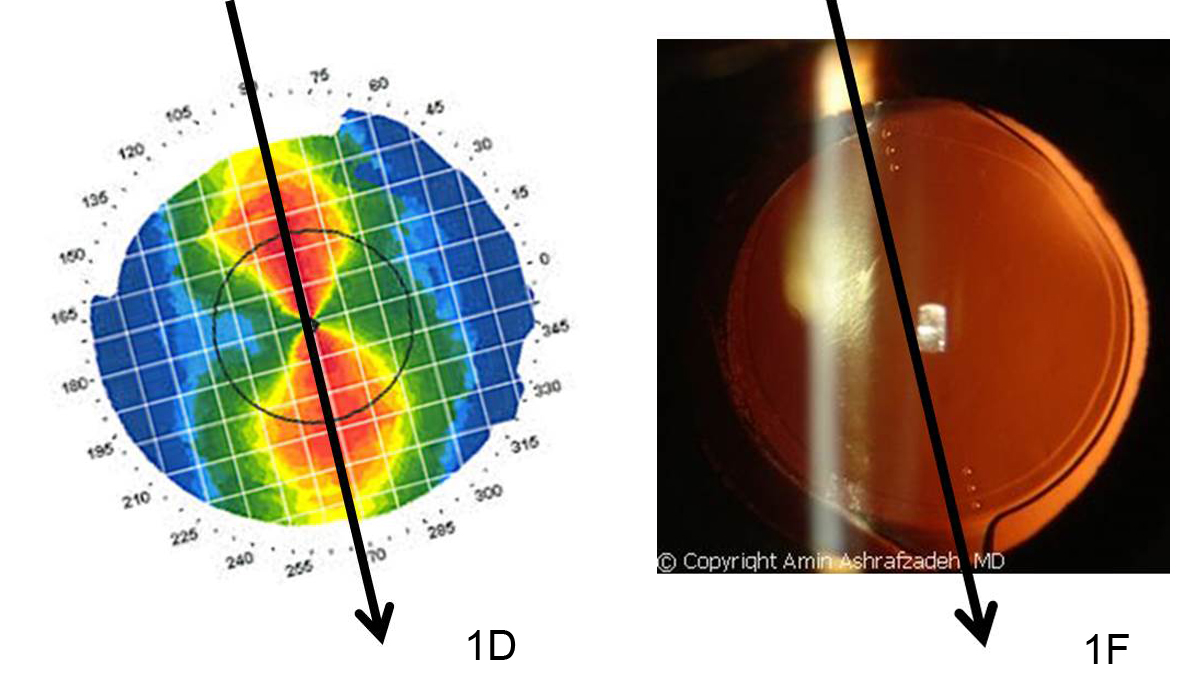

- 4) LipiView II – This test allows us to Image of the structure and function of the meibomian glands in vivo. The images obtained allow for several things. First, we are able to determine the extent of meibomian gland dysfunction. Second we are able to determine the extent of meibomain gland drop out (image 2).

- And third we are able to educate our patients so they can see the importance of treatment of their MGD. Again, this information can help us custom tailor treatment options for the individual patient.

In conclusion, as you can see diagnosis of ocular surface disease can be quite intricate. We are fortunate to be in and age where there has been significant improvements in our tools to help us better diagnose our patients and use this information to individualize treatment options. Stay tuned for the next installment of this blog focusing on treatments for ocular surface disease.

8/20/15

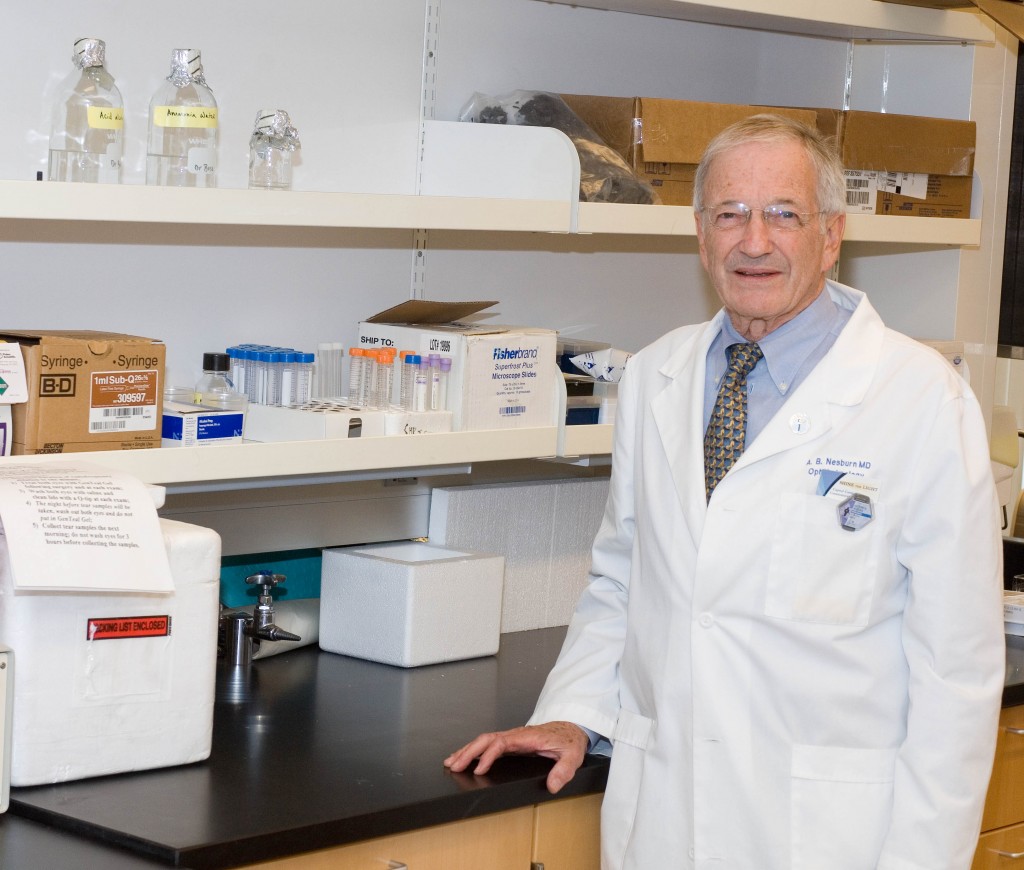

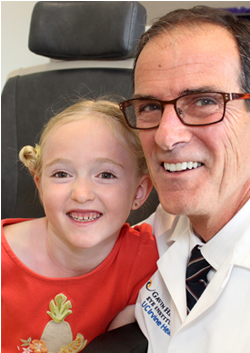

Sumit “Sam“ Garg, MD

Sumit “Sam“ Garg, MD

Medical Director and Vice Chair of Clinical Ophthalmology

Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology

Gavin Herbert Eye Institute – UC Irvine